As part of our article series on the global shift from Service as Action to Community Engagement in International Baccalaureate (IB) schools, we focus here on explaining the first of the four new community engagement learning objectives: Students will explore systems and develop awareness of their roles within these (IBO.org).

Systems thinking is an important part of community engagement because it enables students to see themselves as part of a larger whole, rather than as isolated individuals. It also encourages students to critically analyze and evaluate how the components of a system are related to one another and come together to create a complete entity. According to Professor Edward Crawley, Ford Department of Engineering and Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, systems thinking prompts students to “engage in the unknown and think differently about the relationships between the parts that make up a system; ultimately, learners evolve from reductionist thinkers to integrative thinkers” (MIT.edu).

We are teachers who are trying to change the education system to meet the needs of the 21st century by teaching about systems thinking. As we become more aware of the systems that we are a part of, we aim to help our students become more mindful of the systems that they are a part of, and to see how their actions impact people, animals, and the environment. According to Gitanjali Paul from the Institute for Humane Education, “When schools teach students to become systems thinkers and allow them to practice these valuable thinking habits, they become better prepared to transfer their learning both within and beyond the classroom to address our world’s complex challenges, consider the consequences of their ideas and actions, and positively impact their communities and world” (IHE.org).

Here are a few key questions driving our inquiry:

What does systems thinking look like in action?

Systems are defined by their boundaries and what is within them. Many injustices in the world stem from systems that are wounded or broken, like food systems in many regions. When we think only about ourselves, ecosystems collapse. If we want our students to become agentic changemakers, we must teach them how their actions, large or small, affect the many systems to which they belong. By engaging in systems thinking, new possibilities emerge.

Five years ago, at Munich International School (MIS), students began analyzing their local food system. This inquiry was prompted when a neighbor, who worked at a local bakery, shared that she was tasked with throwing away leftover bread each day. This seemed quite wasteful, especially considering that food insecurity is a problem in Germany. She thought that the students might be able to do something about it. Thus began a multi-year, multi-layered effort to engage students, community members, cafeteria staff, and gardeners in trying to address these systemic problems: food waste and food insecurity.

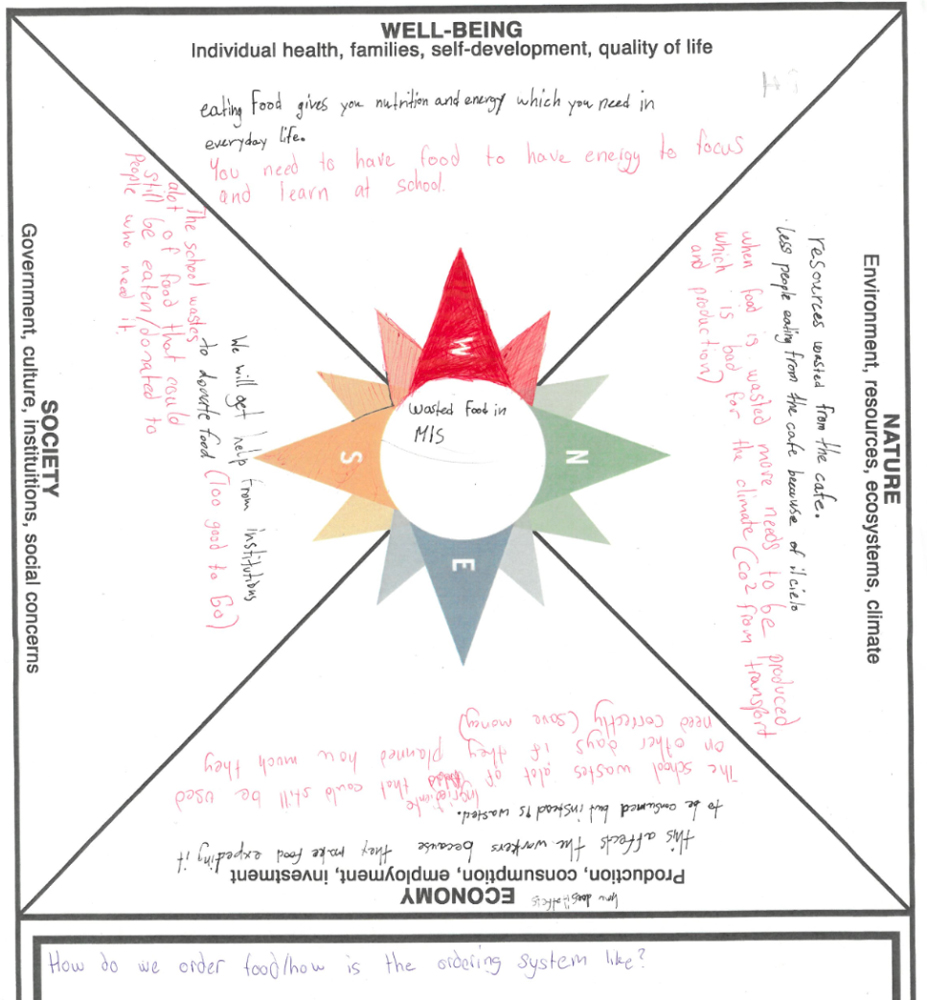

To learn more about the problem they had identified, the students conducted an investigation. They organized their ideas on the Sustainability Compass. They generated inquiry questions such as: “What is the ordering system like at our school cafeteria?”

The students conducted research and became more aware of the multiple laws, people, and mindsets at play when food is thrown away at school and in the local community. Some things that they found out were that, according to the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, around 10.8 million tonnes of food waste are generated annually (as of 2022). The students also learned that in Germany, “3.8% of the population in 2021 experienced food insecurity” (Prevalence of Food Insecurity). Students created documentaries in their English classes to share what they had learned about topics they cared about. Some students chose to talk about food insecurity. Hyun, a Grade 9 student, said, “We don´t have a shortage of food, we have a surplus of indifference.”

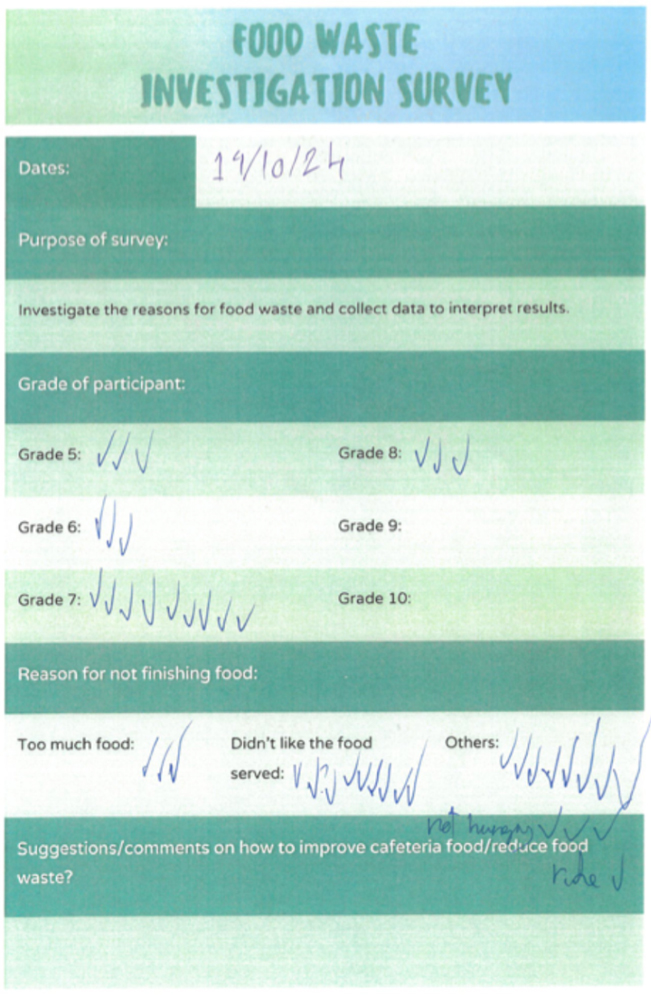

The investigation process continued into the next school year. A lead student collected data about food waste during several middle school lunches, which was then shared with stakeholders at a newly established Cafeteria Committee meeting.

After investigating the systemic issues related to food waste and food insecurity, the students innovated and implemented a few solutions. One idea was to create cookbooks with recipes for old bread. The students also asked the cafeteria staff to help them start counting food waste by volume in the cafeteria to try to reduce the amount of student waste created every day, prepared a survey about student lunch choices (and learned that students who pack their own lunches waste the least amount of food), and interviewed people within Germany who were creatively cooking with food waste, like the organizations Food That´s Left and Too Good To Go.

The food waste reduction initiatives gradually became integrated: curriculum, as a year-service theme; a middle school raised-bed garden began producing vegetables; and in the community, as the students began to see themselves as part of, and responsible for, taking action on the problem. According to Jennifer Bransberg-Englemann, a leader in the Regenerative Economics movement, a natural outcome of systems thinking is an increased awareness of the importance of the commons, a way that people organise to meet human needs outside of markets and the state. Jennifer writes, “The commons are more than just shared resources; they are living systems where communities come together to meet their needs while nurturing relationships with one another and the environment” (Regenerative Economics). When we care about the systems that we are a part of, we want them to be healthy and whole, and to benefit all beings. Learning about food waste and food insecurity at MIS helped students to see the food system and themselves as a part of wider social and ecological systems, and they worked together to address some of the social and ecological issues they found within that system. This took time and effort. Change did not happen overnight.

Once a system starts changing for the better, the effects multiply on their own accord. This is synergy! For example, years after her middle school service project on food waste, one MIS student started her own organization, Replate, to reuse food from grocery stores and provide food to people facing food insecurity.

How can teachers develop systems thinking?

1. Amoeba StrategyOne way to develop systems thinking and positive changemaking is to use the Amoeba Strategy. This strategy, outlined by Alan AtKisson in his TEDx talk, How to be a more effective agent of change, discusses the different roles people play in an organizational or community system and explains how new ideas are adopted and embraced by a system. For a written overview of the model, see Where do you fit on the 'amoeba map'? written by Axel Klimek for Trellis magazine.

The diagram below shows the Amoeba Strategy. Once students become familiar with it as a framework for analyzing and approaching systemic change, they can think strategically about how to create change in a system by using the people who are “change agents” and “transformers” for support, and by steering clear of the people who are “reactionaries” and “controllers.” The Amoeba Strategy helps students visualize how change occurs in a system and what potential roadblocks they might face in implementing change. It also illustrates the power of one person, or a small group of people, to improve a system.

2. Systems Iceberg

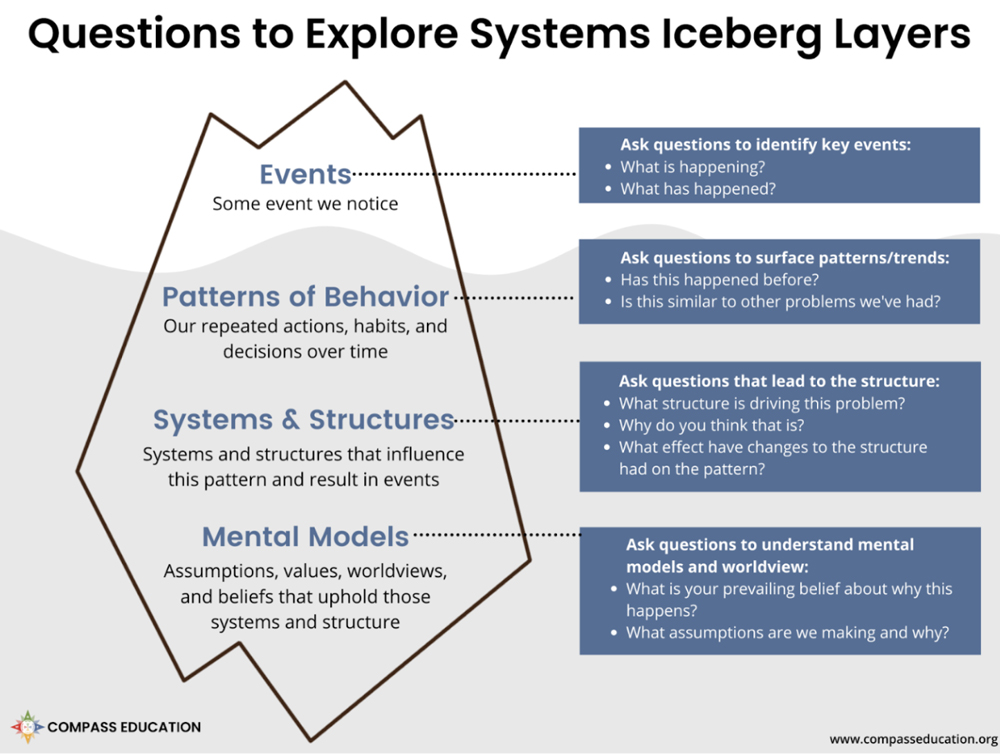

Another way to develop students’ systems thinking abilities is to use the Systems Iceberg. This is a tool from Compass Education that “can help us better understand why things happen, and discover how we can take action to create powerful change” (Compass Education). Using the Systems Iceberg to analyze a situation can help students explore beyond the surface layer and look into the root causes of problems in systems. Instead of just thinking about what the problem is, students begin to think more about why there is a problem and how their actions might be contributing to it.

Using a tool like the Systems Iceberg is a good way to make systems visible. Once a system becomes visible, it becomes easier to pinpoint nodes where changes can be implemented. Additionally, looking beyond the surface helps us move past quick-fix, band-aid solutions to bigger, more sustainable changes. That way, when students propose ideas to improve a system, they are more likely to be structural instead of superficial. For example, the kids at MIS could have donated canned items to a food bank to address the food insecurity issue. But food banks are not long-term, structural solutions. Programs like Replate that seek to connect grocery store and restaurant “waste” to people facing food insecurity are much more effective as long-term, community-based, integrated solutions.

Many additional systems-thinking models can support positive changemaking and systems awareness in young people. An impressive list of case studies and resources curated by UNICEF can be found here.

Challenges, Questions, and Next Steps

We are doing the next generation a grave disservice if we pass over the study of the systems that we are all a part of. Systems thinking encourages taking a step back, looking at the whole of something, and figuring out how to make it better. We acknowledge some of the challenges educators may face, such as limited time and curricular restraints, and the wonders they may have, such as “Where do I start?” when incorporating a systems-thinking lens in their classrooms.

Here are some ideas for where to start:

Those of us who grew up in traditional school systems may find this work messy and complicated because it's nonlinear. The best advice we can offer to teachers interested in weaving more systems thinking into their curricula is to start small. As the Amoeba Framework illustrates, change occurs only when a few brave innovators, change agents, and transformers enter a system, try something new, build momentum, and then persuade mainstreamers to adopt the change. We encourage readers to adopt a systemic lens in their work and life, and let us know how it goes.

Read more about Exploring the Shift From Service Learning to Community Engagement and The Four Components of Community Engagement.

Kathryn T. Berkman currently works at Munich International School. She began her journey as a teacher after graduating from the University of San Francisco, focusing on social justice and multiple intelligences in math education. She has had the opportunity to teach middle schoolers across three countries over the last 13 years. Kathryn is keen to engage in opening the Solutionary lens and framework for educators in different contexts.

LinkedIn: Kathryn T Berkman

Meredith Robinson is the Middle Years Programme community engagement coordinator and English Language Acquisition teacher at KIS Bangkok. Her career overseas has taken her to multiple countries where she has worked across primary and secondary school in roles often involving service learning and action, sustainability, and Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging (DEIJB).

LinkedIn: Meredith Robinson

Megan Vosk teaches the Middle Years Programme, Individuals and Societies, and English Language Acquisition at Vientiane International School. She is also the community engagement coordinator there. Additionally, Megan is a member of the Association for Middle-Level Education (AMLE) Board of Trustees.

LinkedIn: Megan Vosk