Over the years, international schools have seen a paradigm shift in how we foster multilingualism and practice inclusion. Earlier teaching and learning programs were driven by monolingualism and English-only approaches to learning and demonstrating an understanding of that learning. Today, there is much greater acceptance of multilingualism. Schools are beginning to recognize that if we want to truly approach each learner and the learning process with an asset-based philosophy, we must rethink how we have done things in the past. To adjust to these changes, schools have increased the sizes of their specialist and support teams. They are also embracing co-planning and co-teaching models to support multilingual learners in their content area classes and to support teachers with implementing translanguaging pedagogies.

As teachers of multilingual students, we are excited about these changes. They are steps in the right direction. We would like to continue to advocate for policies and practices that support and empower multilingual students and their teachers. With this in mind, here are a few ways schools can successfully transition from monolingualism to multilingualism approaches.

Relationships and Events

Multilingual students need to feel safe and encouraged in their learning spaces, not just in their English language acquisition classrooms or with their English as an Additional Language (EAL) teachers. Students need support to move beyond reluctance, hesitation, and silence towards participation.

Forging connections with students at the start of the school year and making that a priority throughout the year will go a long way in offering students the support and encouragement they need to come out of their comfort zone, move beyond fear, and take a more active role in the learning process with vigor.

Strengthening communication with parents and organizing events that center around language and culture also promote a respect for multilingualism and help the community see multilingualism as a superpower.

International Mother Language Day is held annually on February 21 and is celebrated in many schools across the world. At Megan’s school this year, students marked the occasion by researching and sharing the story and origin behind their names (see the Canva template we used here). Making this a tradition in your school, if it is not already, along with other initiatives such as hosting a schoolwide International or United Nations Day, can help foster multiculturalism and multilingualism.

Instructional Moves

Here are a few of our favorite, go-to instructional approaches to foster multilingualism and empower multilingual learners.

Translanguaging

Translanguaging is an essential component of a multilingual approach. As Ofelia Garcia stated, “To translanguage is to speak naturally and freely, without regard for the restrictions established by the boundaries of named languages, without heed for the constraints that give dual names and borders and limits to the bilingual’s unitary competence” (Garcia, 2018).

In his article The Emergence of Translanguaging Pedagogy, Jim Cummins describes five Linguistically Appropriate Practices (LAP) that teachers can use to support translanguaging in their classrooms. These include:

At Megan’s school, the English Language Acquisition team has been researching “Leveraging Translanguaging Pedagogies” as part of their action research project. The research has led to wonderful insights and the sharing of ideas around what translanguaging looks like and what teachers can do to bring more translanguaging practices into their content area classrooms, such as by encouraging multiple modes of contribution. This means that when students are doing activities like chalk talk or shared brainstorming on paper, they are encouraged to contribute in any way they feel comfortable, including images and other languages.

Each component has its respective features. All eight components are interrelated, and at the heart of these components is explicitly teaching language objectives and making content comprehensible in a language-rich classroom, enabling students to develop academically while growing in language proficiency. Since all these components are interrelated, it’s hard to say which one is more important than the other. That said, if we focus on comprehensible input using effective strategies and scaffolds, everything else begins to fall into place. Some simple and low-prep strategies can be found in the next section.

Andrea Honigsfeld and Jon Nordmeyer, in their article, Collaboration: Working Together to Serve Multilingual Learners, describe effective collaboration between specialist and content-area teachers as a cyclical process that includes co-planning, co-teaching, co-assessing, and co-reflecting. The more specialists and content area teachers work together in all steps of the process to support multilingual students, the better.

For example, at Vientiane International School, EAL teachers regularly meet with a student support teacher to co-plan lessons. At the meeting, they talk about the Lesson Goal and Lesson Reflection, the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles of Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression, and the implementation of the lesson and what role the co-teacher will take in the instruction. At the American Embassy School, New Delhi, the elementary school has put structures in place that allow for regular co-planning and co-reflection on the quantitative and qualitative data. Based on these reflections, the grade-level teams adjust plans for the following weeks so that all students thrive and feel successful.

Resources and Tools

Teachers can empower multilingual students through activities and actions that seek to cultivate students’ self-advocacy skills. Oftentimes, multilingual students are navigating new systems, frameworks, and contexts. Whereas international schools tend to value concept-based, holistic learning, many traditional public schools in students’ home countries still prioritize rote memorization and direct instruction. The gap between what learning “looks like” in different school settings can cause newcomer multilingual students to feel confused and isolated. Thus, the importance of building self-advocacy skills is paramount so that students can ask for help and voice their questions.

The following graphic is a teaching tool for helping multilingual students learn how to self-advocate. It shares five ways that students can self-advocate, such as by sending an email to a teacher when they don’t understand something. Self-advocacy skills need to be explicitly taught and modeled to multilinguals, and students need to be given opportunities to role-play and practice. This is especially important if students come from schooling backgrounds where they have been expected to “sit quietly” and receive information, rather than speak up for themselves. For more information on cultivating these skills, see Megan’s recent TIE article, Cultivating Students' Self-Advocacy Skills.

Infographic: “Self-Advocacy Tips for Students.” (Photo source: Megan Vosk)

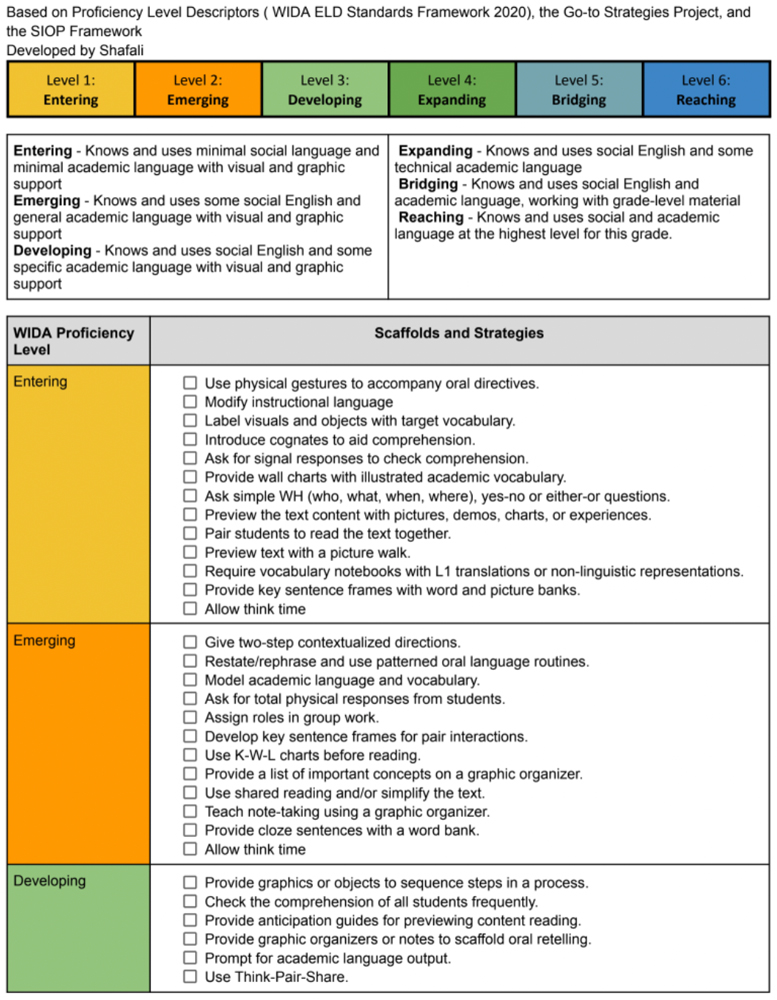

Scaffolds and Strategies Continuum for Teachers of Multilingual Learners: This continuum provides easy, low-preparation strategies designed to support teachers of multilingual learners. These scaffolds and techniques are intended to reinforce the eight core components of the SIOP model while aligning with students' proficiency levels across all language domains.

Conclusion

We are heartened to see all the positive ways that language instruction and respect for multiple languages and cultural identities have improved over the years. We hope these trends will continue and that schools will one day fully embrace supportive and inclusive practices. The tides are shifting away from more isolated modes of language instruction. But there is still work to do.

Some questions that remain are:

For these questions, we acknowledge that there are no specific answers. They deal with complex and multifaceted issues. However, if we keep them in the forefront of our minds as we strive to meet our schools’ missions, visions, and values, we will surely continue to do, and be, better for our multilingual learners and their families.

Megan Vosk teaches the middle years program, Individuals & Societies, and English Language Acquisition at Vientiane International School. She is a member of the Association for Middle-Level Education (AMLE) Board of Trustees.

LinkedIn: Megan Vosk

Shafali is a multilingual learner specialist at the American Embassy School in New Delhi. She has been on the virtual review panel for the WIDA ELD Standards Framework, 2020 Edition. Her work has also been published in Andrea Honigsfeld and Maria Dove's book, Co-Planning.