--------------------------------------------------------------

Engaging in team sports can equip students with a diverse skill set that translates to classroom success. Skills such as effective communication, collaboration, and social skills are just a few examples. I have been privileged to witness and nurture this development firsthand through my involvement in team sports during my K-12 education at the American School in Japan, and later as a coach in locations including Honduras, Bahrain, and South Korea. As educators, we have a unique opportunity to extend our influence beyond the traditional confines of the classroom. Through extracurricular activities like sports, we can forge deeper connections with our students, broadening their educational experience while fostering their personal growth. In this article, I aim to delve into two subjects that I hold close to my heart and explore their intersections - the realms of culture/identity and sports.

Identity is a concept I regularly contemplate. I often examine what constitutes identity, my own sense of self, and the meaning of being "truly Japanese" or "truly American." This subject resonates deeply with me as someone with a Japanese mother and an American father who grew up in Japan while receiving an American education at an international school. In the realm of sports, this subject emerges when mixed-race athletes must decide which country to represent. The conversation can also vary depending on the specific sport in question. For instance, the worlds of baseball and soccer have notably different requirements for representing one's nation in international competitions.

In soccer, regulations are stringent. According to the Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) statutes, "A player may only represent one nation at the international level, provided they hold the nationality of that country." Additionally, there are inflexible rules regarding playing for multiple teams. Once a player has represented a national team, they are forbidden from switching to another. This often leads to a "tug-of-war" for young athletes eligible to represent multiple countries. A prime example is Adnan Januzaj, who was qualified to play for Belgium, Albania, Kosovo, Serbia, and Turkey due to factors such as birthplace, parental heritage, and grandparents' origins. Players must choose carefully, as they are barred from representing any other country once they have made their decision.

In contrast, for baseball, in order to represent a nation, one does not need a passport. Instead, they can fulfill this requirement in one of two ways; either the player has at least one parent who is, or if deceased was, a citizen of the Federation team’s country or territory, or the player has at least one parent who was born in the Federation team’s country or territory. Until the recent World Baseball Classics, I believed that possessing a passport should be a prerequisite for representing a nation. This seemed logical to me because I wondered how someone could genuinely represent a country if they are not officially recognized as a citizen.

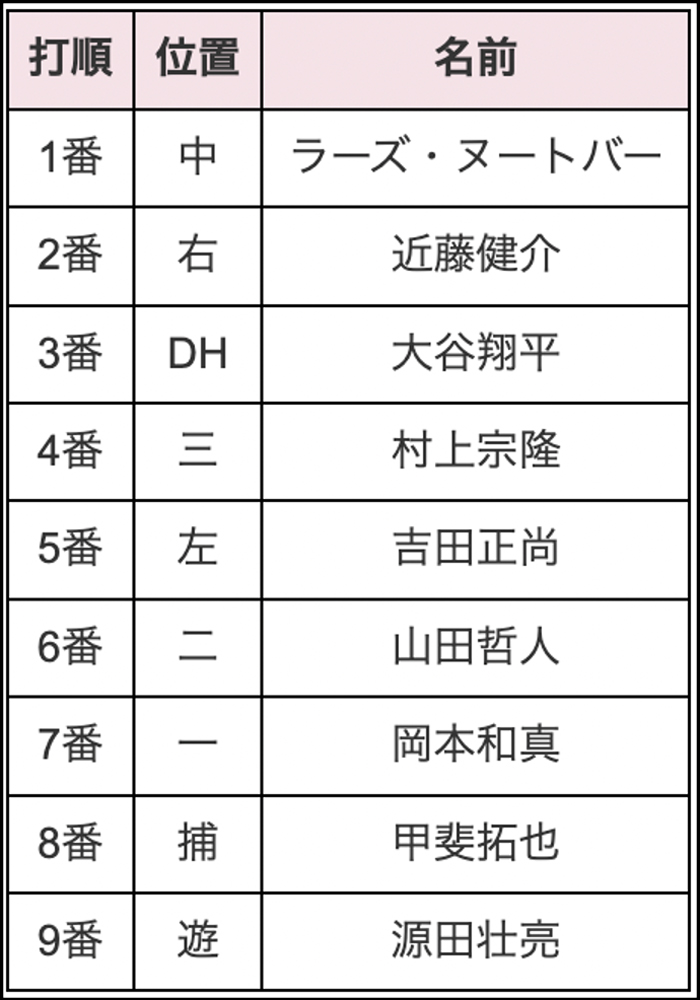

In late January 2023, the Japanese national team revealed their selection of 30 players for the upcoming tournament. Below is a glimpse of the starting lineup for the squad. You may observe that one of the names appears distinct from the others.

Indeed, the first name features significantly fewer intricate characters compared to the subsequent eight. This is Lars Nootbar, whose name is written using katakana カタカナ, the script typically used by foreigners to spell their names (apart from certain athletes who have Japanese passports, but with foreign fathers). My name, like Nootbar, is similarly spelled using only katakana: ハリス・ニコラス (Harris, Nickolas). Nootbar is Japanese American. He was born and raised in the USA but has Japanese roots on his mother’s side.

Despite this connection I found to Nootbar, I found it difficult to wholeheartedly support his inclusion on the team. He did not speak Japanese and had not visited Japan for the past twenty years. It seemed to me that he wasn't "authentically Japanese," and I wasn't alone in holding such reservations. At first, there was some reluctance to welcome this gaijin 外人 into the fold. Former players like Hisanori Takahashi questioned Nootbar's selection, arguing, "There are Japanese players just as skilled who could have been chosen instead." This statement insinuated that the coaches should have preferred a Japanese national over the Japanese-American Nootbar if presented with the option.

During that week, I stumbled upon a short documentary about Nootbar. It explored his Japanese heritage, tracing it back to his mother's lineage. Despite his inability to speak Japanese, he had always felt a strong connection to Japan. As early as his elementary school days, Nootbar was determined to represent Japan in baseball. The documentary included footage from 2006 when a nine-year-old Nootbar confidently proclaimed his Japanese identity and asserted that he represented Japan while playing for his little league team. Born and raised in California, Nootbar's deep connection with his Japanese ancestry fueled his lifelong dream of playing for Japan. In his heart, he was Japanese.

I felt remorse for creating preconceived assumptions about his identity, culture, and loyalty to Japan based solely on his passport. Despite the fact that I am a Japanese passport holder, I've encountered individuals throughout my life who disregarded my Japanese identity or labeled me as "not Japanese enough" due to my physical appearance, name, or mixed ancestry. This realization made me see that my initial rejection of Nootbar was a reflection of the attitudes of those who doubted my own nationality. In doing so, I unintentionally imposed my own criteria on another person's identity, failing to consider their unique experiences and emotions.

International schools often champion aspirations such as "creating global citizens." In this increasingly interconnected world, as educators, we have a crucial responsibility to recognize and appreciate the various identities and cultures which our students represent. We navigate the dynamic landscape of classrooms where students' identities resonate in many ways. Some students identify with their birth countries, while others feel a stronger connection with the nations where they were brought up. Furthermore, there are also students who align themselves with a country where they neither were born nor spent significant time.

With seven hits and four runs batted in, as well as numerous outstanding plays in the outfield, Nootbar quickly established himself as an invaluable asset to the Japanese team. His charisma also made him a fan favorite among the national team members. Baseball enthusiasts across Japan warmly referred to him as "Tachan" (たっちゃん), a nickname derived from his middle name, Tatsuji.

The Lars Nootbar story demonstrated to me that identity transcends the limitations of a mere government-issued document. Possessing a passport was never the exclusive determinant of his "Japaneseness." Nootbar identified as Japanese and was willing to give 100 percent for the Japan national team. I used to be skeptical of the baseball system that permitted players without a passport to represent their nation. However, Lars Nootbar's journey has made me reevaluate this stance.

Nootbar is as Japanese as I am, regardless of whether he holds a Japanese passport or not. As teachers, we are responsible for understanding this diverse spectrum of self-identification of culture and respecting the individual ways in which students articulate their identities. Reflecting on a personal note, despite my own bicultural and international upbringing, I too grappled with biases when someone didn't align with my preconceived notion of being "fully Japanese." As previously mentioned, I questioned Nootbar's identity because he did not fall into the category of what I considered "truly Japanese." Such moments of introspection and questioning our own viewpoints are essential as we teach about culture and identity in our rapidly globalizing world, especially in our often very global classrooms.

The concept of "identity" is prevalent for many mixed-race children and third-culture kids (TCKs) as they navigate their lives. As international educators, we often teach students who are of mixed race or considered TCKs. The website, Identity-Centered Learning, is a valuable resource for educators to help effectively address the topics of race and identity. This platform is managed by Daniel Lee-Wickner, a mixed-race educator and fellow "hafu," who teaches at Hong Kong International School.

References

(FIFA) Fédération Internationale de Football Association. "Regulations Governing the Application of the Statutes." FIFA Statutes, FIFA, [Publication Date], www.fifa.com/about-fifa/official-documents. Accessed 23 April 2023.

Answer編集部 : The. “ヌートバー、侍Jを「家族」と表現した粋な円陣 海外絶賛「彼は全試合でやるべき」.” THE ANSWER スポーツ文化・育成&総合ニュース・コラム, https://the-ans.jp/wbc/307370/.

週刊女性Prime . “【WBC大活躍】「決して選ばれる選手ではない」ラーズ・ヌートバー選手への‘酷評‘に批判殺到の高橋尚成氏が謝罪も「許しません」「上から目線」収まらない野球ファンの怒り(2ページ目).” 週刊女性PRIME, 11 Mar. 2023, https://www.jprime.jp/articles/-/27163?page=2.

“【選出理由】ヌートバーはなぜ日本代表?5つのポイントが評価!?” Kininaru Blog, 9 Mar. 1970, https://aiolin.com/nutoba-naze-japan/.

Wickner, Daniel. “Identity-Centered Learning: A Framework for Educators.” Identity-Centered Learning, https://www.identitycentered.com/.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Nickolas Hironao Harris teaches Advanced Placement (AP) psychology and AP research at Korea International School Jeju in South Korea.

Website: www.nickharrisjapan.com