Why does this practice matter?

The practice of “copying the masters” has deep roots in artistic training. Historically, Indian artist communities worked in a studio setup where teachers and students of different age groups, gender and often family members worked together to complete an artwork. They never signed their work since it belonged to the entire artist community. Similarly, apprentices in the ateliers of Europe worked from the masters’ own sketches, drawings, or paintings, learning the language of their craft through repetition and immersion. The very term atelier evokes this tradition of master-and-pupil working side by side.

When students examine, for instance, how a master built up a figure with thick strokes, or thin washes, or blocked in color, or layered glazes, or oriented the light subtly—they decode the decision-making behind the flourish. In doing so, they train their eyes, their hands, their minds. In my classroom context, when a student chooses to recreate a Van Gogh painting, they naturally begin asking: What materials did he use? Why did he paint this way? What are his strokes like?

From this perspective, the activity becomes more than imitation, it’s investigation. And this exactly feeds into the new International Baccalaureate Diploma Program visual arts course of Art Making through Inquiry. In other words, we consciously teach the students to ask the right questions during the art-making process.

However, another question that I often face from my students is, “Isn’t it plagiarism?” Let’s explore that.

Addressing concerns about plagiarism and the difference between learning and copying.

It is understandable that some feel uneasy about the idea of “copying” another’s work, but clarity of purpose matters. Copying becomes problematic only when the student tries to pass off the result as an original creation of their own.

The key distinction lies in intention:

“Learning from” means the student is using the master’s work as a lens to ask questions, to try and trace the technique, and to adopt the process as a way of thinking.

Copying to claim means the student merely duplicates the form without reflection, and worse, tries to present it as their original.

So, it seems that it is entirely acceptable if one is copying the work of a long-gone master artist to inquire. However, can they copy a living artist’s work? I would say yes, if the intention is about understanding and learning and not claiming it as their own. In both the cases, the work is presented as an artist study with citations. In other words: a master study is a study, not a plagiarism. The focus is skill-building, not appropriation. It is accepted and encouraged in the art world as a tool for growth, not as a shortcut to authorship.

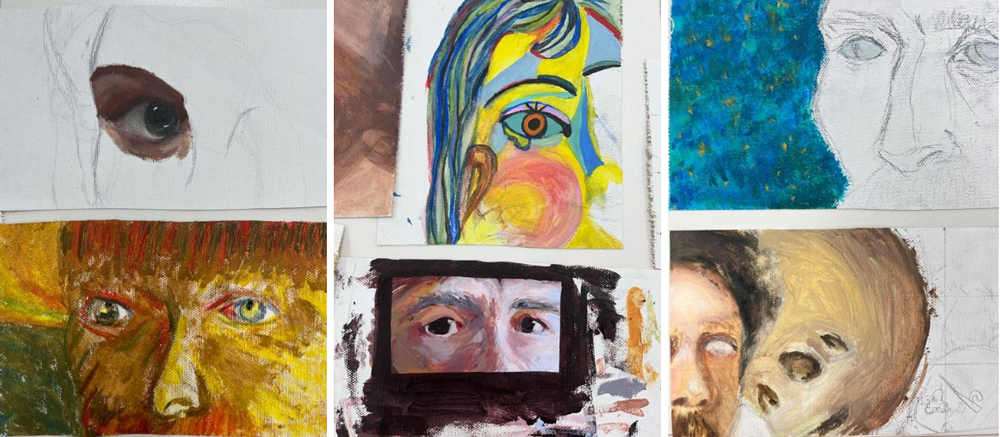

Student work-in-progress study patches. (Photo source: Dr. Debjani Mukherjee)

So, what does the student actually learn through this exercise? Here are some of the layered benefits.

Technical fluency: By replicating a small section of a painting, the student learns how the master handled paint, brush-pressure, layering, glazing, underpainting and so on.

Visual empathy: The student begins to see with the master’s eye. When replicating a fragment of texture or modelled form, they experience the decisions of composition, light direction, line quality, colour harmony.

Critical thinking: Good copying is paired with inquiry: What did the artist do here? Why did they handle the shadows that way? What happens if I try their palette but apply more contrast? Thus, copying becomes a doorway to deeper conceptual understanding.

Creative translation: After the study is complete, the student is in a stronger position to create their own work. The journey isn’t about mimicking forever, it’s about absorbing lessons so they can internalise technique and then express their unique vision.

Mind-hand connection: By working physically with paint, brushes, surfaces, the student builds muscle-memory, sensitivity to materials, and an embodied understanding of the craft.

Even though it is a simple exercise, it can often be tricky to set the guidelines for students' expectations and open their mind to art making through inquiry, reflection, internalization, and finally the implementation of the study in their own artworks. So, here’s how one might structure this practice in a studio or classroom setting.

A step-by-step, practical guide for classroom implementation:

Suggest to students that they observe an artwork carefully and then select a fragment. Rather than copying a full large painting, pick a manageable patch, perhaps the hand of a figure, a section of drapery, or a small background of reflective light.

Use guided observations. Guide students to ask questions: What are the brush-marks like? How thick is the paint? What is the direction of light? What is the palette? What’s the key value?

Replicate the patch. Students should attempt to reproduce that fragment, taking time to mix colors, layer glazes, apply brush-pressure; they can challenge themselves to change the original medium to another more manageable one.

Reflect and journal. After their attempt, prompt students to reflect: What surprised me? What did I struggle with? What did I learn about the artist’s process?

Transform it into an original work. Once the study is done, invite students to create their own small piece inspired by the technique but transferring it to their own subject, palette or concept—thus moving from study into creation. At this stage the content of the subject could be very different from the original artwork.

Emphasize credit and intention. The study should be clearly labelled (e.g., “Study after …”). Encourage your students to annotate their study with what they learned, what surprised them, and how it may influence their next original piece.

Finally, in my classroom, I encourage my students to share their work-in-progress study patches. Each patch becomes a visible record of inquiry, patience, observation, and transformation.

Student work-in-progress study patches. (Photo source: Dr. Debjani Mukherjee)

The goal is not to copy forever but to be able, when the time is right, to use all that has been learned to create anew. So, slowly, one study at a time the students begin to see like an artist, ask like a learner, and create like themselves.

Dr. Debjani Mukherjee is an International Baccalaureate Middle Years Programme and Diploma Program art and design teacher working at Gems World Academy, Dubai.