I’m not an English teacher but my work, every single day, lives in the world of seeing. I’ve often told my students that drawing, painting, and creating are not simply acts of making, they are acts of seeing. But when of my students asked me, what do you mean by “acts of seeing?" This question became the spark for one of my favorite classroom explorations: The Art of Seeing.

Starting with a Single Word

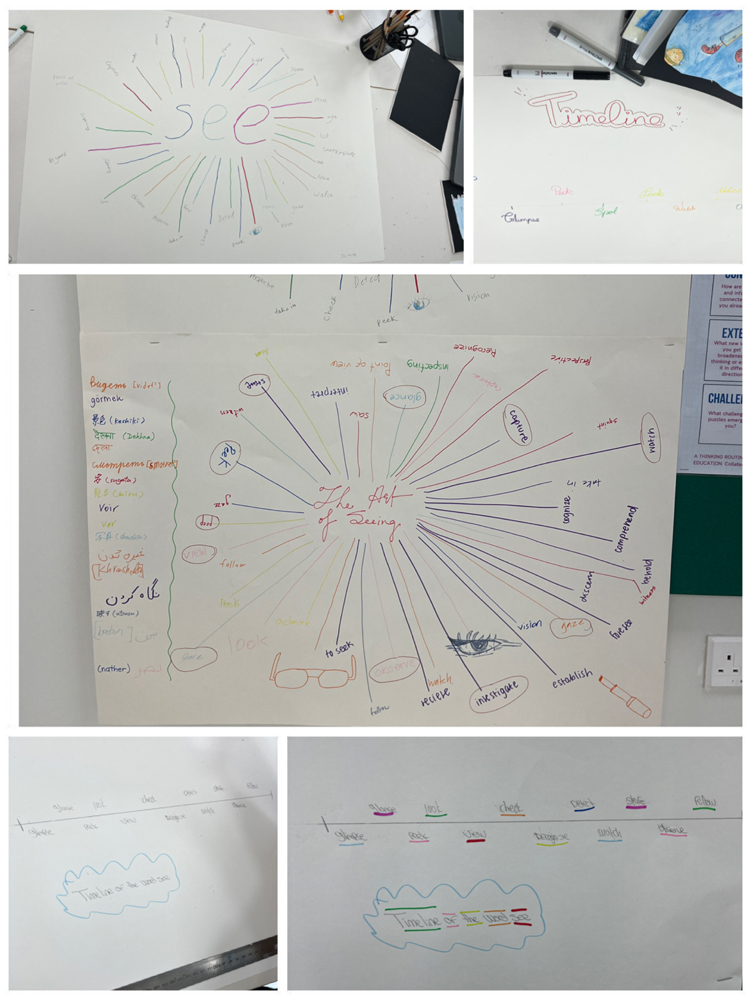

On an ordinary afternoon, I wrote the word SEE in the center of a large white sheet and asked my students to respond, “What are the other ways we can say this word?” At first, they hesitated. A few said, look, watch, observe, notice. Soon the ideas began to flow: gaze, peek, glance, stare, glimpse, behold. The art room slowly filled with colorful lines connecting the central word see to a web of its siblings, each carrying its own rhythm and tone. Then came the surprise. One student raised her hand and asked, “Can we add words from our own languages?” That question changed the direction of the exercise entirely, something that I had not planned before.

The Classroom Turns Multilingual

As soon as I said yes, the atmosphere transformed. Students began scribbling translations in their mother tongues — Arabic, Hindi, French, Tagalog, Korean, Mandarin — next to each English synonym. Each new word brought a story. One student explained that in her language, there’s a word that means “to see with curiosity,” while another described a term that translates to “to see and silently admire, but not say a word.” We realized that the act of seeing is not just a sensory function, it’s deeply emotional, cultural, and intentional. The simple act of collecting words had turned into a shared exploration of perception. Collage of a class brainstorming session. (Photo source: Dr. Debjani Mukherjee)

Collage of a class brainstorming session. (Photo source: Dr. Debjani Mukherjee)

Mapping the Journey of Seeing

To push the exploration further, I challenged them to create a timeline, a visual journey from fleeting to focused seeing. They arranged words like glance, peek, and glimpse (brief, almost accidental acts of vision) at one end. Then came look and view, leading to observe and watch (which require patience and intention). Finally, they placed study, inspect, and contemplate at the far end (words that spoke of depth, reflection, and sustained attention). As they built this visual map, the students began to recognize how language captures the gradations of awareness. The subtle shifts between each word mirrored the stages of the creative process itself, from initial spark to deep observation.

From Words to Vision

By this stage, curiosity had taken over completely. Students began to compare how seeing functions differently in art versus everyday life. One said, “When we draw, we don’t just see — we notice what others might ignore.” Another added, “Even the word we choose changes how we look at something.” And that was the heart of it. This wasn’t just a vocabulary lesson; it was an art lesson in disguise. Students were learning how perception shapes understanding, how observation is more than visual intake; it’s an act of empathy, of connection, of meaning-making.

What the Exercise Revealed

By the end of the session, every student had contributed their words, drawings, and reflections onto their large sheets. It was truly inclusive as even the English as an Additional Language (EAL) students found their voices heard and appreciated. Some illustrated their mind maps with eyes, glasses, magnifying lenses, even telescopes — showing the many ways humans try to “see better.”

What struck me most was how this activity opened up further questions on awareness. Students began asking: What does it mean to truly see an object or a person? Do we always see what we expect to see? How does language limit or expand what we notice? In other words, they were beginning to think like artists — reflective, observant, and questioning.

The Afterglow

Later, as we displayed the posters around the art room, students walked around, comparing and laughing at the diversity of words. One remarked how similar some words were across languages, while another marveled at how some meanings simply did not exist in English.

The discussions that followed were organic, thoughtful, and deeply engaged, all growing from a single, everyday word.

Why It Matters: Teacher Reflection

This exercise reminded me that in art education, seeing is never just looking. It is noticing, feeling, interpreting, and imagining. It’s about slowing down in a world that moves too fast, and discovering that vision is both external and internal.

By exploring The Art of Seeing through language, my students learned that every act of observation is layered with thought, memory, and culture. They learned that the language we use to describe vision also shapes the way we create and express it. And for me, it reaffirmed something essential about teaching art: that learning to see, truly see, is the first step to learning to create.

As a teacher, I learned how the use of these different words began to shape meaning for my students in unexpected ways. I could see the sensitivity they developed quite consciously when I used different “seeing” words in class, from creating a glancing contour sketch to catching the action lines of people in motion to a detailed portrait study, or a self-observation drawing.

They began to sense that each task had its own rhythm, its own way of seeing — quick, attentive, or contemplative. It made me realize how language subtly directs perception, and how our choice of words can alter the creative mindset.

This experience also aligned beautifully with the IB’s interdisciplinary (IDU) approach, bridging language and visual arts to deepen conceptual understanding. It celebrated our multicultural classroom, where each language added a new lens to perception, and it embodied authentic learning where curiosity, meaning, and expression came together naturally. In the end, it wasn’t just my students who learned to see differently, I did too.

Dr. Debjani Mukherjee is an IB Middle Years Programme and Diploma Program art and design teacher working at Gems World Academy, Dubai.