As educators, parents, and mentors, our ultimate goal is to help the young people in our care grow into empowered, capable, creative, and ethical individuals. We teach them to read, write, calculate, and explore science, history, and the arts - all the probable tools they will need to succeed. But there’s one critical subject we often overlook, or perhaps even avoid: power.

Power is often seen as a sort of taboo topic, forcing us to confront some uncomfortable realities about how society truly functions. It reveals the dynamics of relationships - at home, in the classroom, at work, and also within larger societal structures like cities and governments. Yet, power is neither inherently good nor bad. Its essence lies in how it is understood, wielded, and navigated.

“Power is not something that is simply wielded; it is something that is exercised. Power is not something that is held by one individual or group, but rather a relation of force that moves through every layer of society.” — Michel Foucault

The multitude of power dynamics work all around us, all the time. And in the school setting, power can significantly impact both students and their learning! So, what if we, early on, help our students better understand the many ways power manifests, not only within the school, but in society as a whole? Can we help them take their first steps in traveling the road that will show them how power flows and functions, perhaps a bit like Foucault described? If we take the steps ourselves to overcome our own discomfort in addressing this topic, we aid the students in becoming more aware and able to adapt to the many power structures they will encounter. If we look closely, we can see that significant efforts, such as diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice (DEIJ) initiatives, have already been attempting to address power imbalances, like those seen in bullying. Smaller instances, like asking to go to the bathroom, deciding who gets to be the line leader, or sharing toys, also shape students’ perceptions of authority and agency.

So how could we try to dissect and analyze power so we can help students of all ages explore the many ways it manifests and affects all things? It is a tricky subject and downright challenging - and as I've mentioned, to some, delicate. This was the challenge and focus of the new exhibit at Escola Americana do Rio de Janeiro's (EARJ) MuseOn, our ongoing, pioneering educational project that started in 2007. In this space, we craft educational installations with impacting, provocative themes that are meant to resonate with important current affairs or possible futures. Students experience a learning journey every time they come to this space. The shows are carefully planned to connect with as many curricular units as possible, thus becoming both a teaching as well as a learning tool. And since conceptual, open themes are used, connecting to the many classes and subjects becomes not only more efficient but also can work better with the International Baccalaureate (IB) framework.

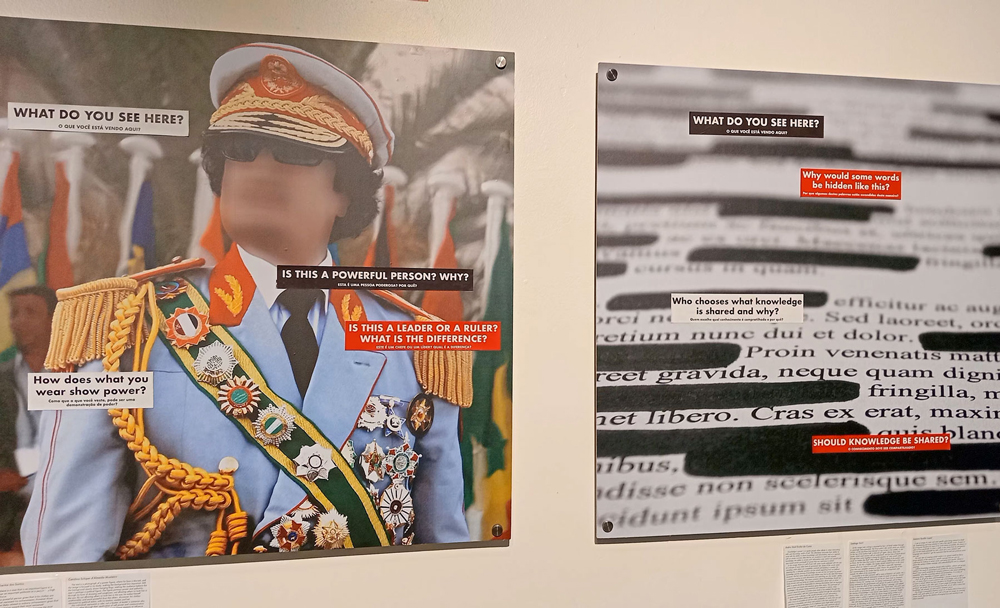

Now in the new exhibit, “Power - User’s Guide,” we aimed to openly discuss the many ways power works and the multitude of ways it manifests itself, from talking about the sun, energy, geopolitics, and religion, to even the politics of migration. The exhibit consisted of a series of images and objects that may seem uncommon or even mundane, but each one holds a story of much power. Simple things like a ball, a bag of flour, and like/love social media symbols, were meant to invite the students to discern their relations to power.

An example of some of the questions and provocations made at the exhibit. (Photo source: Daniel Whitaker)

Each image and object had a series of questions or provocations provided to the students, such as:

These and many other questions were fuel for dialogues, exchanges of ideas and views, and engaging debates that took place at the exhibition space.

Because the nature of the theme can be dense, and to maximize student comprehension, efforts were made to adapt the content to all age levels, using different approaches that increased in complexity the older the students were. The objective, naturally, was to enable students concerning power and to help them understand that they are not only pawns but also actors, who wield power in small and sometimes huge ways affecting the lives of others as well as themselves. And that they are endowed with the power of choice, a strong example of power, that can work in small or impactful ways.

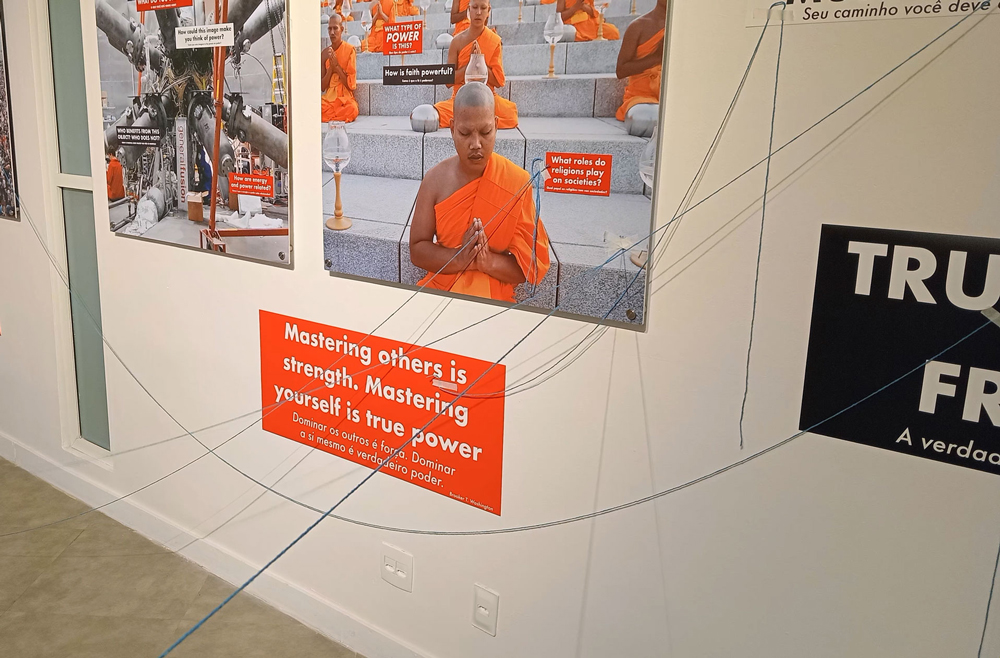

Student-made connections about power during the activity. (Photo source: Daniel Whitaker)

One of the ways we encouraged the students to investigate the horizon of the possibilities of power was to have them make their own connections by choosing three items shown in the exhibit, be it an image, object, quote about power, or even another peer’s work. Using strings, students created a visual web of interpretations and physical connections to these three items that they later had to justify and explain, enabling their critical thinking and dialogue ability.

The “Power - User’s Guide” exhibit wasn’t just about presenting information; it was about sparking active conversations about this important topic. By encouraging students to engage in respectful debate, we aimed to not only foster a culture of critical thinking but also inspire them to be able to engage with other, future complex subjects. Through this learning journey and the debates they had, the students gained an increased perspective of how things essentially function.

Let us imagine a future where students are not merely passive recipients of knowledge, but active agents of change. We can inspire young people to challenge injustice, advocate for equity, and build a better world by fostering a deep understanding of power dynamics. The “Power - User's Guide” exhibit is just one step towards this goal. By the end of their visit, students leave with a heightened awareness of the multifaceted nature of power, recognizing its potential for both harm and good. They emerge empowered, ready to navigate the complexities of the modern world and contribute to a more just and equitable future.

Daniel Whitaker is an educator and the MuseOn curator at EARJ in Rio de Janeiro, a pioneering educational project in the form of a museum-like space. He is passionate about investigating the blurred lines of transdisciplinary thought and focuses on inspiring curiosity, debate, and critical thought through the creative educational installations he builds in the museum spaces of the school.