Technology integration is defined as “using technology including computers, digital cameras, compact disks, held devices, probes and related technologies to deliver and enhance the curriculum already in place” (Pitler & Bartley, 2004 cited in Bataller 2018). In an effort to expand the understanding of technology in education, the International Society of Technology in Education (ISTE) developed a set of standards that can drive innovation in the learning environment across different roles (e.g., educator, student, coach, leader, etc.) at school. The ISTE standards for students, for instance, pointed out seven areas that can help better prepare the students for the demands of the 21st century such as empowered learner, digital citizen, knowledge constructor, innovative designer, computational thinker, creative communicator, and global collaborator; each standard has a set of criteria to further help the educators learn how to implement the standards. There are also many models used to understand how to integrate technology. The most popular ones are:

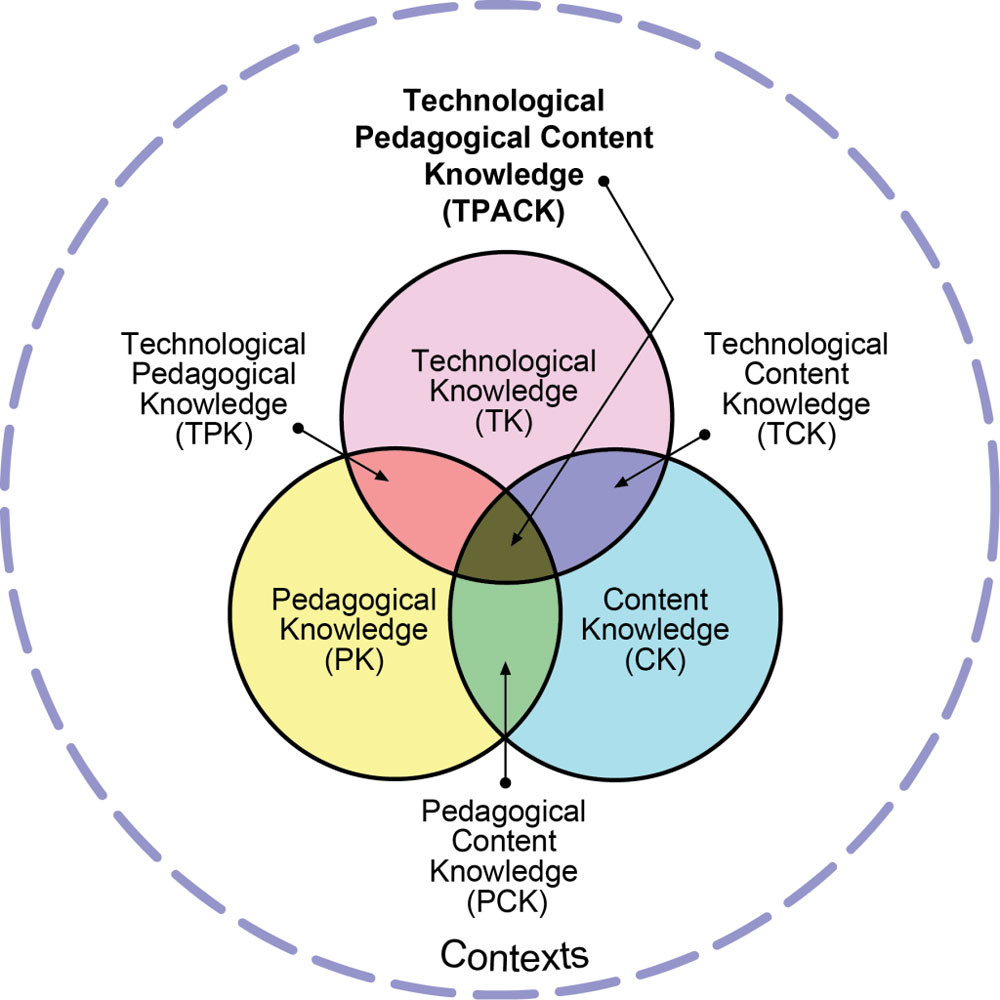

1. The Technological, Pedagogical, Content, and Knowledge Framework (TPACK)

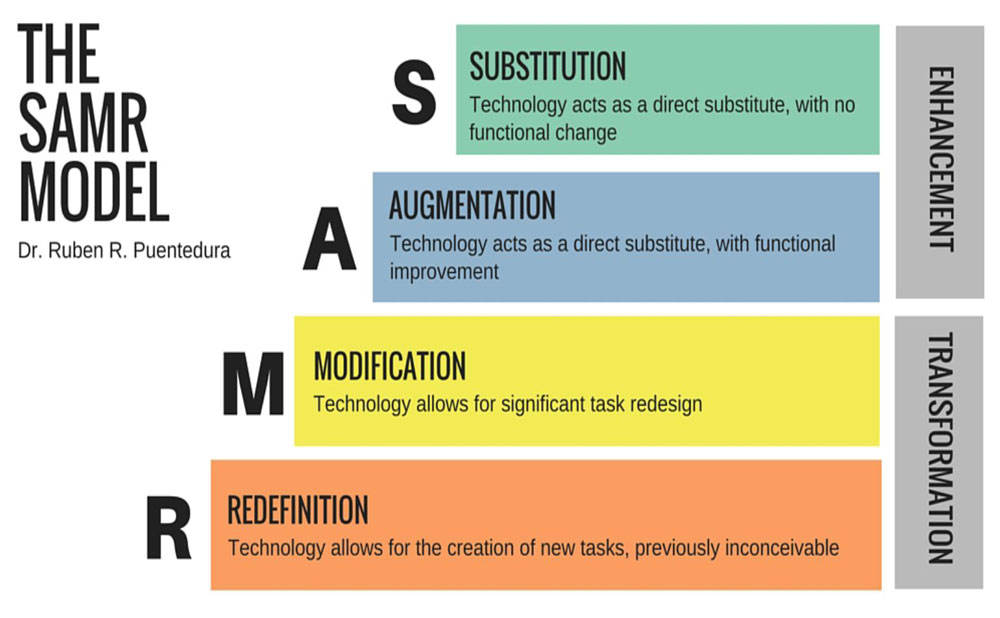

2. The Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, and Redefinition (SAMR) Model

(Photo source: Lefflerd, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

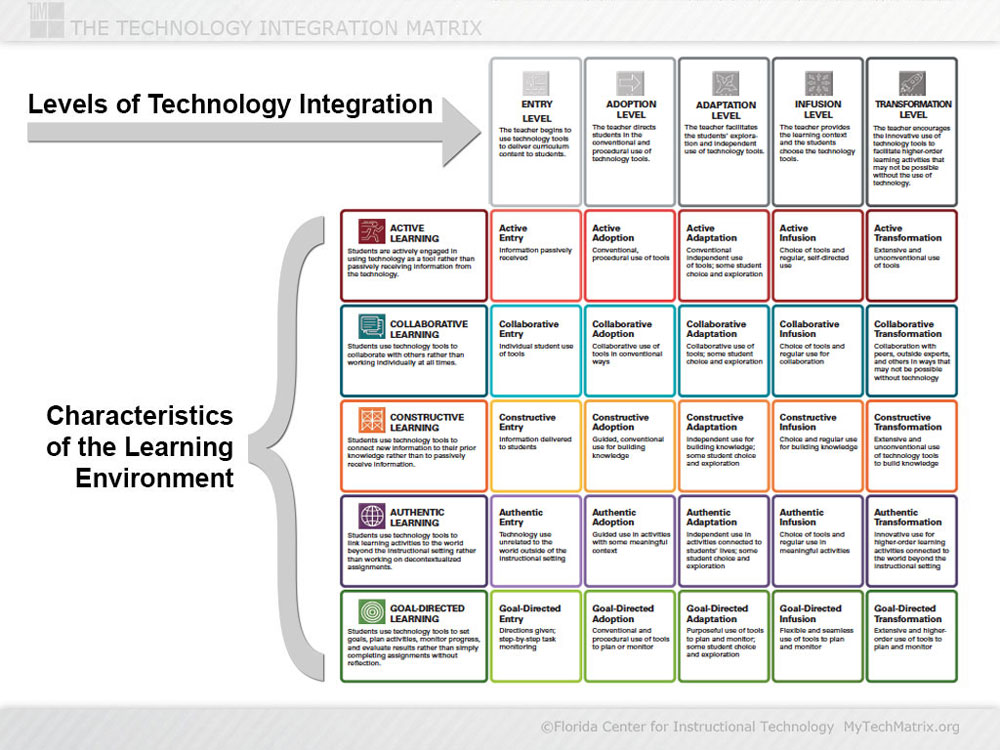

3. The Technology Integration Matrix (TIM)

(Photo source: The Florida Center for Instructional Technology, fcit.usf.edu)

Obstacles to Technology Integration

Many researchers say that integrating technology in the classroom can help the students attain skills needed to succeed in a diverse, complicated, and highly innovative world, driven by access to many different types of information. Expanding access to different cultures, when implemented successfully, can lead to developing authentic learning both for the students and the teachers (Edutopia, 2014; Ito, 2013; Luckin, Bligh, Manches, Ainsworth, Crook, & Noss, 2012).

Because of the fast-paced nature of technology, teachers who are viewed to be the change agents sometimes find themselves unable to understand which application is truly effective in their classes (Fullan, 2013; Bataller, 2018). And considering the high cost of implementing technology at schools and the time it takes to train the teachers, it is important to find out the different obstacles that might hinder the successful implementation of technology (Greenridge & Walcott, 2020).

There are many surrounding debates as to what can prevent technology in education from being integrated successfully, despite the presence of many technological devices. Among the many identified factors are the teachers’ attitudes, knowledge and understanding, personal characteristics, the school’s overall mission and vision, and school support.

Attitudes:

One theory is that teachers’ attitudes are the reasons why technology fails (Christensen 2002; Teo 2008; Yalcin, Kahraman, and Yilmaz 2011). Some teachers don’t approve of or appreciate the value technology can offer a classroom and their behaviors directly impact the level of success they have with integration. Some other teachers feel that integrating technology should be optional instead of recognizing it as a normal part of the curriculum (Nicholas 2018).

Knowledge and Understanding:

Another theory, (Yalcin, et.al. 2011), however, identifies that teachers will only be able to impart to the students the usefulness of technology when they themselves understand how and when to use it. Therefore, if the teacher has only general knowledge of computer use, it will be challenging both for the teacher and the students to feel that it has enriched the lesson (Greenridge & Walcott 2020).

Personal Characteristics:

Other studies (e.g., Buabeng-Andoh, 2012; Elsaadani, 2013; Rana, 2013 as cited in Greenridge & Walcott, 2020) showed that teachers’ personal characteristics could be a factor. They posit that age, gender, prior experience in the use of computers, and years of teaching affect the success of technological integration.

Overall Vision and School Support:

A number of other studies pointed out additional factors that impacted integration. Schools lacking in an overall vision for technology obstruct programs to support teachers in using technology (Hew & Brush (2007). Teachers’ tight schedules give them very little time to learn emerging educational technologies (Kopcha 2012) and without school support, it is difficult to make the time. Limiting policies and regulations (Alenezi 2017; Ihmeideh 2018), institutional structures, scarcity of resources and funding (Bataller 2018; Liu & Pange 2015), and the digital divide (LEAD 2012) are also all contributing factors.

Overcoming the Obstacles:

Although many researchers have attempted to explore this topic, the construct of effective technology integration is still “vague and complex” (Bataller 2018). The ISTE standards and different technology integration models are still the best source of knowledge to guide the educators to integrate technology effectively; however, they will need support from their organizations to overcome obstacles, like shaping the school’s overall vision with the technology in mind, creating responsive policies and procedures, crafting matched professional development programs to develop teachers’ competencies, and creating opportunities to increase the level of comfort and confidence of educators in the use of technology. The research-based frameworks, TPACK, SAMR, and TIM, are a way toward overcoming the current challenges in technology integration. These frameworks provide practical approaches for integrating technology into the existing curriculum of an international school.

The Covid-19 pandemic has changed the way many schools and educators view the importance of using technology. No matter where you are along this journey, it is vital to understand that technology integration will continue to be our reality well into the future. As more educators join the conversation, we will be able to support each other in overcoming the obstacles and have more effective technological integration in our schools.

References

Alenezi, A. (2016). “Obstacles for teachers to integrate technology with instruction.” Educational Information Technology, 22, pp. 1797–1816. DOI 10.1007/s10639-016-9518-5

Bataller, C. (2018).” Technolgy integration: A mixed-methods study of best practices of technology integration as perceived by expert middle school teachers.” [Doctoral dissertation, Brandman University].

Christensen, C. M. (2011). “Disrupting class: How disruptive innovation will change the way the world learns.” Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Books.

Edutopia. (2014). “Technology integration: What experts say.” Retrieved from http://www.edutopia.org/technology-integration-experts

Fullan, M. (2013). “Stratosphere: Integrating technology, pedagogy, and change knowledge.” Toronto, Canada: Pearson Canada, Inc.

Genota, L. (2018). “Why Generation Z learners prefer YouTube lessons over printed books; video learning outranks printed books in survey”, Education Week, No. 1.

Greenridge, G. & Walcott, P. (2020). “Assessing the attitudes of Dominican primary school teachers toward the integration of ICT in the classroom.” International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology, 16(2), pp. 84-96.

Ihmeideh, F., & Al-Maadadi, F. (2018). “Towards improving kindergarten teachers’ practices regarding the integration of ICT into early years.” Asia Pacific Educational Research, 27(1), pp. 65-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-017-0366-x

“ISTE Standards: Students.” ISTE, https://www.iste.org/standards/iste-standards-for-students.

Ito, M. (2013). “Hanging out, messing around, and geeking out: Kids living and learning with new media.” Cambridge, MA. The MIT Press.

Kopcha, T. J. (2012). “Teachers’ perception of the barriers to technology integration and practices with technology under situated professional development.” Computers & Education 59, 11091121. Retrieved from http://marianrosenberg.wiki.westga.edu/file/view/KopchaTTeachersPerceptions.pdf

Le, P.B., Lei, H. and Than, T.S. (2018). “How leadership and trust in leaders forster employees’ behavior toward knowledge sharing.” Social Behavior and Personality: an International Journal, Vol. 46 No. 5, pp. 705-720.

Leading Education by Advancing Digital Commission. (2012). Retrieved from http://www.leadcommission.org/about-lead

Lei, Hui, et al. (2019). “How to Foster Innovative Culture and Capable Champions for Chinese Firms.” Chinese Management Studies, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 51–69., doi:10.1108/cms-05-2018-0502.

Liu, X., & Pange, J. (2015). Early childhood teachers’ perceived barriers to ICT integration in teaching: A survey study in Mainland China. Journal of Computers in Education, 2(1), 61–75.

Luckin, R., Bligh, B., Manches, A., Ainsworth, S., Crook, C., & Noss, R. (2012). “Decoding learning: The proof, promise and potential of digital education.” Retrieved from https://www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/decoding_ learning_report.pdf

Nicholas, Samira. “ Obtacles and challenges to integrating technology in the classroom: Perspectives from teachers in a Lebanese context” International Journal of Arts & Sciences, vol. 11, no. 1, 2018, pp. 425–440.

Teo, T. (2008). “Pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards computer use: A Singapore survey.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 24(4), 413-424.

Terada, Youki. “A Powerful Model for Understanding Good Tech Integration.” Edutopia, George Lucas Educational Foundation, 4 May 2020, https://www.edutopia.org/article/powerful-model-understanding-good-tech-integration.

Winkelman, Roy. “Tim Levels and Characteristics Slide.” TIM, https://fcit.usf.edu/matrix/project/tim-levels-and-characteristics-slide/.

Yalcin, Sema Altun, et al. “Primary School Teachers of Instructional Technologies Self-Efficacy Levels.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 28, 2011, pp. 499–502., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.096.

Yasir, M. and Mohamad, N.A. (2016). Ethics and morality: comparing ethical leadership with servant, authentic and transformational leadership styles. International Review of Management and Marketing. Vol. 6 No. 4S, pp. 310-316.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Roselyn Pastorfide Baronia teaches AP computer science subjects, is a whole-school content leader for IT instruction, and is the school-wide technology integration coordinator at Tsinglan School in Dongguan, China.