EMILY: I was giving a training series on privilege and marginalization for a large international organization this summer. During one of the sessions, a Black man shared about a time when, as a student at a prestigious American university, he was studying in the library, when a White man about his age approached and asked if he actually attended the school. When the participant confirmed that he was, indeed, a student there, the White man turned and walked away without another word.

“Classic microaggression,” I said aloud.

The participant looked up at me through our Zoom screens and said, “Microaggression? It felt more like a full-on aggression to me.”

My chest tightened when I realized what was happening. What would you do in this situation, Daniel?

DANIEL: I would apologize for misrepresenting his experience and ask him, if he is willing, to share more about how the encounter felt, how he responded, and what it meant to him. At least I would like to think that I would respond this way.

Although a natural instinct may be to defend our intentions, I believe it’s important, especially in these moments, to show humility, deference, and genuine interest in the realities of others.

How did you end up responding? And how did it play out?

EMILY: That’s good advice, and I wish I had done that. Instead, I choked. My eyes got wide: “Oh! I didn’t mean micro in that way!” I made myself and my intentions the focus, and then I think I tried to explain what I meant by microaggression, basically intellectualizing his lived experience. Not my best work. Keep in mind, this was during a training seminar on privilege and marginalization that I was leading. I knew better!

DANIEL: I’ve had similar moments (which I too am not proud of), as I’m sure many other antiracist allies have had as well. Being multiracial, I can relate to this situation from both sides— as a person of color who has had others misrepresent my reality and as a White person who has, at times, unintentionally misrepresented the realities of others. That moment of disconnect can be an inflection point in any discussion, and it’s how participants— particularly the “misrepresenter”— respond that can determine the relationship of the participants going forward.

That feeling of panic and the need to explain ourselves— where does that come from? I contend that it’s from the cognitive dissonance between our impact (racist words, actions, systems) and our perceived intent (non-racist or anti-racist).

In fact, “being antiracist” may even have become part of our identity— how we see ourselves and how we want others to view us— and having a racist impact clashes with the core of who we believe ourselves to be. The panic is a mini identity crisis, of sorts; and we feel the need to neatly realign everything in the presence of the POC we just harmed.

EMILY: You put that really well. Thankfully, I knew this (intellectually), and did manage to recover from my mini identity crisis in time to staunch the bleeding, so to speak. I wish I had caught myself sooner, but it just goes to show that, even when we are relatively cognizant of the issue, we can mess up.

I’ve had many conversations with White educators whose mini identity crises drag on because the fixation on our intent will never resolve the impact of our actions. We White people are used to being centred, and our feelings and comfort are usually protected. To prioritize our impact means setting aside our feelings and intent, and focusing instead on those of the people of color experiencing our words and actions. The good news is that this can be done! And I feel really grateful to partner with you on this project.

DANIEL: Yes, me too! We were getting deep into a discussion about identity and inquiry (another important topic), but I think we realized that there were some fundamental core pillars of DEIJ that needed to be addressed first -- and were more actionable and relatable for the majority of educators not already involved in this work.

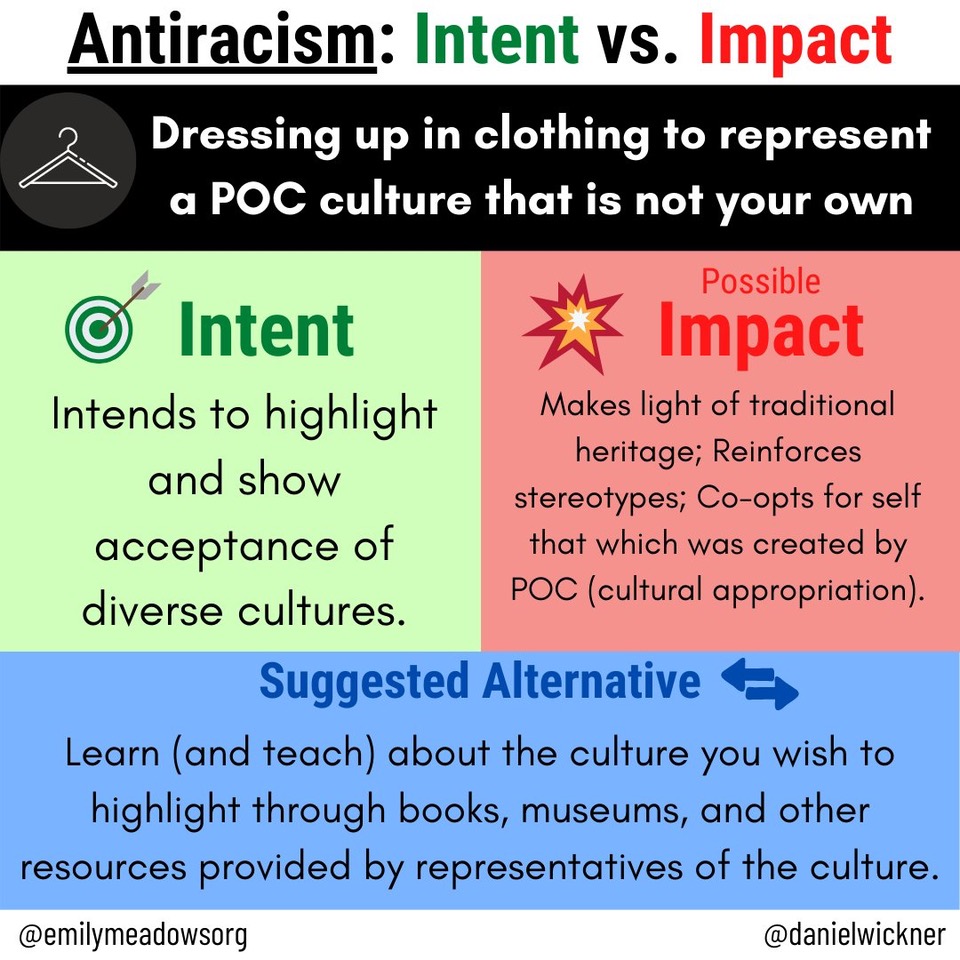

As you mention, differentiating and navigating between one’s intent and impact can be challenging for many White allies, myself included. And, like with any new skill we learn, it’s good to see a series of examples to help us grasp it more tangibly. That’s where our idea for the #IntentVsImpact infographics came from.

EMILY: We’ve tried to cover some common issues like colorblindness, reverse racism, and cultural appropriation, as well as some concepts that folks may be less familiar with. I hope our infographics series will resonate with readers, and that it will be useful as a tool for educators working to make their practice more antiracist.

DANIEL: Agreed. Antiracism is more than just a series of behaviors to avoid; it’s a fundamental mindset shift in how we approach everything we do as educators— and scrutinize, confront, and transform the structures and systems that we inhabit and uphold. My hope is that these infographics will help facilitate that vitally important shift.

Please find Daniel and Emily, along with their new infographic series on Antiracism Impact Vs Intent, on Twitter:

@DanielWickener

View the full: #ImpactVsIntent Gallery