Given the myriad of approaches to whole school change that exist today, why exactly should a school choose Restorative Practices? Schools are faced with many initiatives that can be embraced that make many claims to improve systems, enhance social and emotional learning, and improve academic outcomes. Many of these programs share the same concepts and theorists, yet are packaged differently, often appearing to be in competition with one another.

It’s beneficial to understand a comparative evaluation of two approaches that schools might embrace: Responsive Classroom (RC) and Restorative Practices (RP). I will examine the interplay between them by identifying the common ground as well as the key differences. I will then proceed to discuss these differences by considering the implications of each and reach a balanced conclusion on which model is most effective for whole school change, with the special consideration of international schools. The gap that I aim to explore centers on the real-world outcomes that each approach can yield. By examining nuanced differences, I intend to highlight the distinct merits and limitations of RP. In addition, I will explore the concept of Restitution and examine how this may enhance the application of RP. The aim is to provide clarity and insight into the rationale behind positioning RP as the most auspicious choice over other viable positive discipline approaches. This exploration strives to equip international school leaders with adequate information in order to make informed choices when considering a school-wide change that is in alignment with the vision, mission, and values.

Explanation of Responsive Classroom

Responsive Classroom emphasizes the importance of community as well as the importance of academic, social, and emotional growth (About Responsive Classroom, 2023). The process of how students learn is of equal importance to what is learned. It is a foundational view that academic achievement is fundamentally linked to building social and emotional competency. RC is supported by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) and elevates the teaching of prosocial skills so they are valued just as much as academics. The core principle of RC is to create a safe and joy-filled learning environment that facilitates learning, risk-taking, and the reaching of a child’s full potential (Responsive Classroom, 2015). It is not a curriculum; rather, it is an approach to teaching. In addition to a proactive approach to discipline, the use of logical consequences, and emphasis on positive language, there are morning meetings, the modeling of good behavior, academic choice, inquiry-based learning, collaborative learning, explicit teaching of both academic and social skills, regular assessments to inform the teacher what works and what may need to be adapted, collaboration with the students over the physical classroom space, concerns for the teacher in managing stress and self-care, and finally, partnering with the local community (Responsive Classroom, 2015b).

Contrasting Responsive Classroom with Restorative Practices

There are many similarities and shared beliefs between RP and RC which are already apparent; therefore, it will be more beneficial to focus on the points of contrast.

It could be argued that the role of consequence is more clearly defined in RC, making it less ambiguous and more certain as to when, how, and why consequences are to be applied.

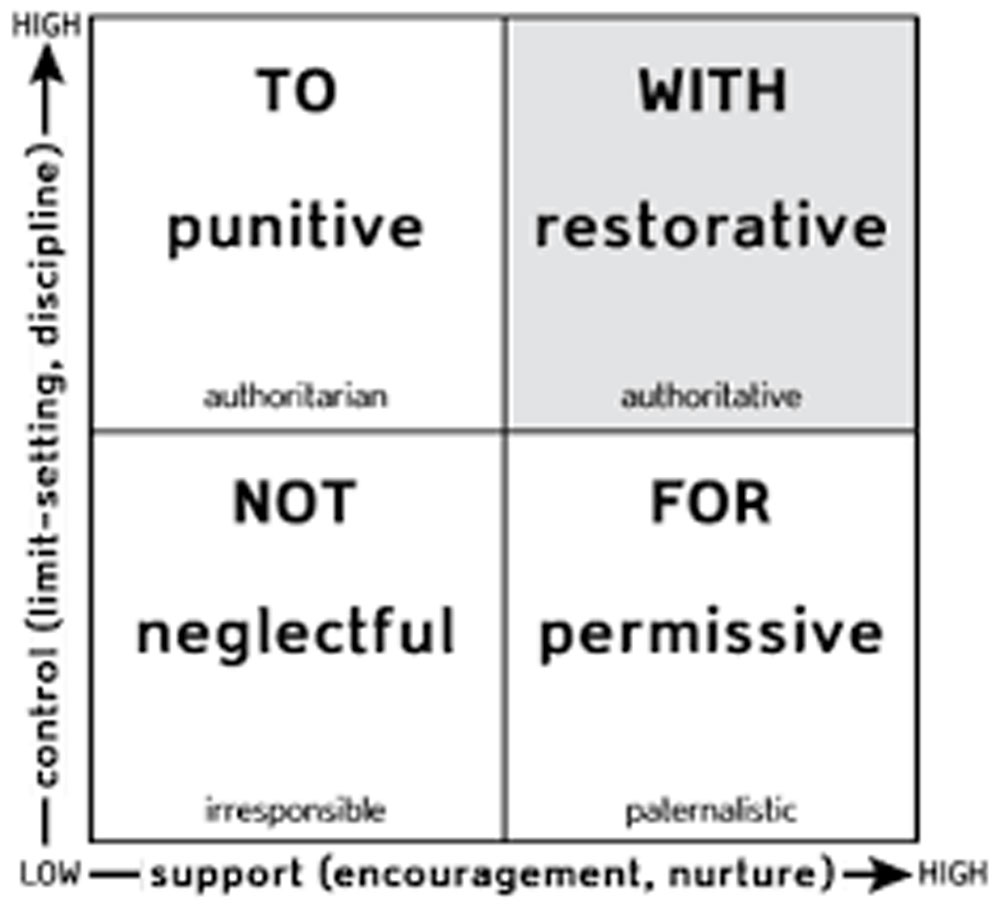

(Photo source: Wachtel & Costello, The Restorative Practices Handbook)

RP teaches that people will make positive changes when those in positions of authority do things with them rather than to them or for them. The RP Social Discipline Window (SDW) is unequivocal that the emphasis needs to be “with” when offering the student high levels of support whilst maintaining high levels of accountability (Wachtel, 2016). From the RP paradigm, RC can be considered as erring towards the “to” quadrant with its emphasis on prescribed consequences, although well intended, as the teacher is usually the one determining and issuing the logical consequence. In contrast, in RP, the starting point is to ask the students what they think needs to happen in order to “make things right,” ensuring the teacher remains in the “with” quadrant of the SDW. However, RC has a lot to offer RP in terms of the role of logical consequences. As discussed earlier, on the occasions where the student is unable to identify “what needs to happen to make things right” then logical consequences come to the fore, and this is where the conceptualization of logical consequences can complement the work of the restorative practitioner. This is significant as it may be an ambiguous aspect of RP for teachers who are new to the approach and who may be unclear on how to proceed with handling behavior issues in these circumstances, resulting in them being too quick to adopt a weak solution put forward by a student who may be seeking an easy way out. If this happens repeatedly, the RP is criticized as the soft “easy” option and suffers from reputation damage in the school community from the perspective of staff, students, and parents who expect accountability and high standards. Therefore, RC offers a useful insight and can overlap with RP, offering a complimentary tool to ensure accountability, on the condition that the RP paradigm emphasis is always on “with.”

Although RC is to be applauded for using circles to facilitate the morning meetings - a clear strength - it is clear that the understanding and application of circles is underdeveloped when contrasted with RP. There is a lack of theoretical underpinning to support the use of circles in RC, whereas in RP there is a rich and diverse body of literature which explains and justifies its efficacy. In contrast to RC, RP proposes a range of circles for use in different contexts, including proactive and responsive. As RP moves from informal to the more formal, mechanisms such as the Restorative Justice (RJ) conference and the family group decision making conference become options for handling conflict through circles, fostering structured processes that encourage open dialogue and accountability. It is clear that although RC values ideas such as involving the community and creating respectful environments, it lacks the specific measures to achieve this to the same extent. RP is able to provide a more sophisticated toolkit, especially with regards to handling conflict. On this point, the key weakness that emerges is that RC does not have the mechanism to handle more severe behavior issues.

RC successfully elevates the teaching of prosocial skills; however, it can be argued that it lacks the mechanisms required to handle conflict. RP benefits from being able to draw from other fields, namely criminal justice, where the concepts overlap and enrich the education sector. RP places a strong emphasis on repairing harm, it addresses not just the immediate behavior, but also has clear approaches and concrete mechanisms to ensure that the harm done to individuals (and the wider community) is acknowledged and resolved. The concepts and theoretical underpinning that enable this approach are lacking from RC, limiting its scope and efficacy. Instead of mitigating conflict, when conflicts eventually occur, RP seeks to transform them into opportunities for personal growth and learning. This is most visible when conducting an electronic search on the EBSCO database. Once the “choose database” option is selected and “all databases” is selected, a search for “responsive classroom” on EBSCO host yielded 1,158 results. In contrast, the search for “restorative justice” yields 6,749 results. It is clear that RP benefits greatly from the RJ literature and is informed by the thinkers and theorists from other fields. This is significant as it explains why RP is more developed in tangible approaches than RC is.

Positive language is prioritized in RC with an abundance of articles which can be found on the RC website that encourage inclusive language, non-judgmental questions, calm firmness and general emphasis on language that drives teacher mindfulness to notice students' efforts and comment upon them (Wells, 2022). These articles are incredibly beneficial and helpful to teachers, with a clear overlap with the RP conceptualization of affective language. However, many RC articles focus on general advice, and it is a clear point of contrast that RP seems to prescribe language to a greater degree than RC does. RC may emphasize the use of non-judgmental language, which is in essence what the affective questions in RP achieve, but it lacks the specific questions for educators to memorize and use when confronted with conflict. It could be argued that RP is more effective here as the restorative question cards are fundamental to daily practice and aid the conversations with clear and concise language that prevent loaded questions from being used. RC may advise that this should happen, but it lacks the clarity and precision that RP offers through affective questions.

Developing the point about the more sophisticated theoretical underpinnings of RP, the use and role of language in RC can be contrasted to further illustrate this. RP clearly draws from the work of Silvan Tomkins and utilizes affect theory in order to provide a rationale for the importance of language. In fact, RP doesn’t just generally imply that positive language is important in general terms, it provides very specific reasons why. Distinguishing between feelings, emotion, and affects, Tomkins has provided RP with a helpful understanding as to why human beings act and respond in certain ways and why RP is effective. Costello et al. synthesize and further enhance the work of Tomkins by introducing Nathanson’s Compass of Shame, Vernon Kelly’s emphasis on maximizing positive affect as well as Braithwaite’s warning against stigmatizing shame (Costello et al., 2009). This provides a compelling understanding of the role of affective language in a way that is lacking from RC.

A fundamental limitation of RC is that it is a K-8 initiative (About Responsive Classroom, 2023). This is limiting for organizations seeking whole school systems change as clearly RC is not designed for older students. In contrast, RP is renowned for its whole school approach and is effective across the divisions, supported by research from the RAND Corporation (Augustine et al., 2018). Whereas RC is limited to classroom strategy, RP is a school wide, cross divisional philosophy that can lead to significant change in behavior management and building community. Therefore, by this measure, RP seems superior when compared to RC when it comes to affecting whole school change.

There is tremendous similarity and crossover between RC and RP in terms of philosophy, focus, responses to behavioral issues, emphasis on relationship building, approach to discipline and shared long term goals to promote social and emotional competencies. It is perhaps a false dichotomy to present one against the other, as in reality schools can select elements of both when devising behavior policies and considering systems change. The two approaches are not mutually exclusive. Perhaps a balance approach that combines elements of both may yield the best results, as is the case in the Chicago Public School Guide and Toolkit (CPS, 2017). However, a search on the EBSCO for “restorative responsive classroom,” once all databases are selected, yields only one result. This implies a surprising lack of research into the interplay between both approaches and indicates a gap in the literature and a clear area for future research.

It is worthwhile to note that RP is the more recent development between the two, and as such, has been mindful of incorporating key principles of RC and other positive behavior approaches into its methods. This is highlighted by Wachtel where he states that, “in education, talk is of ‘positive discipline’ (Nelsen, 1996) or ‘the responsive classroom’ (Charney, 1992); and in organizational leadership, ‘horizontal management’ (Denton, 1998) is referenced. The social science of restorative practices recognizes all of these perspectives and incorporates them into its scope” (2016, p. 2). RP, as an emerging social science, appears to have greater momentum with schools worldwide who are embracing the concepts and benefiting from the sophisticated overlap between the fields of criminal justice and education.

It is evident that RP has broader scope and application. It is enriched by its capacity to draw from the criminal justice field and apply the concepts into education. RC is an impressive school initiative, but when compared to RP, lacks the conceptual depth and theoretical underpinning that RP provides. However, the two approaches are by no means mutually exclusive. Schools may opt to use a framework of supports and interventions to address behavioral and academic challenges, and both RC and RP can work in synergy, perhaps alongside other initiatives such as Aggression Replacement Training (ART) as outlined by Amendola and Oliver (2010) or Restitution Restructuring, as outlined by Gossen (1998). If the wellbeing of the child is central to a school, then multiple approaches can be used in tandem to ensure the student receives the assistance they need.

The Role of Restitution to Enhance Restorative Practices

Criticism of RP often emanates from a view of justice that emphasizes punishment. From this lens, some may view RP conferencing as a soft option when compared to traditional punitive methods. For some stakeholders, the idea of an apology being offered seems to allow students “off the hook” (Fields, 2003). This can be seen in the justice system where there is fierce discussion over what constitutes a fair outcome.

In the context of education, Gossen (1998) refers to “restitution restructuring” as the creation of conditions for the person to fix their mistake and to return to the social group stronger. This approach recognizes that an apology is significant, but in and of itself it is not enough. Restitution restructuring focuses on fixing problems and creating solutions whilst avoiding focus on stigma and blame. Students are encouraged to be in touch with their own emotions and view their negative feelings as signals that help them to focus on their unmet needs. The goal is to encourage students to come up with a plan to fix their own mistakes and repair the harm caused, supporting the child to become the better person they aspire to be. Restitution restructuring means the school “create[s] conditions for the person to fix their mistake and to return to the group strengthened” (Gossen, 2001). In essence, Gossen is emphasizing the importance of teaching children about each other’s needs, building classroom contracts, gaining the support of parents, discussing, and agreeing on class power dynamics, teach children how to "create restitutions" that satisfy the needs of all involved, model self-evaluation, and self-restitution by admitting mistakes and owning behavior.

This model is a valuable addition to RJ as when the criteria for good restitution are followed, the argument that the perpetrator is “off the hook” is no longer compelling. Accountability becomes the focus, which arguably is what most people wish to see happen when wrongdoing has occurred. Gossen’s criteria consist of: the wrongdoer expending considerable time and effort in planning and implementation of restitution; the victim achieving satisfaction from the process and outcome; the choice of a type of restitution that has a clear and logical relationship to the mistake; the strengthening of the wrongdoer’s capacity to behave in ways that contribute to positive relationships with others. When Gossen’s criteria for a good restitution model are followed, the outcome cannot be said to be the “easy option” for the person who has caused harm. When restitution is followed and adopted into the RJ conference, the needs of both the victim and the wider community can be successfully met.

Thus, Gossen’s “restitution restructuring” model, although sharing much in common with RP, can help enhance the implementation of the final stages of the conference when asking “what needs to happen to make things right?”. Gossen’s criteria for restitution help to ensure accountability and avoid criticism that RJ is not a soft option. Given that restitution restructuring is based on the belief that offenders need to take responsibility for their actions and victims are entitled to compensation, it could be argued that neutral observers would struggle to disagree with the accountability that restitution can bring.

Some may argue that this model is limited, as not everyone is willing to engage in good faith with such an approach. Although it can be said that for most people most of the time such an approach can be effective, a realist lens needs to be applied when the perpetrator is seeking to manipulate systems or shows no intention of taking accountability. RJ approaches can be criticized as ineffective in such cases, making advocates of RJ appear idealistic, out of touch, and ineffective. From Gossen’s perspective, it is clear that in cases where students are not ready to engage in good faith with this model, then an approach that emphasizes consequences must be utilized. If the student is not a willing participant then restitution is not effective (Gossen, 2001, as cited in O’Connor and Peterson, 2013). This caveat creates a very pragmatic solution to what should happen when students are unwilling to participate, which may help to reduce the criticisms that can be received as to the weaknesses of RJ. Although the RJ practitioner should desire that everyone has a restorative opportunity, this cannot be forced on those who are unwilling to participate, and from the school's perspective, this is where other mechanisms need to be on offer until such a time that the student is willing to engage.

It is clear that Gossen’s model is complementary to RP and her insights on restitution enhance the effective implementation of RP in schools. With regards to the evidence basis, when checking the EBSCO search database and using the key words “restitution schools” (and selecting “all” for every database option) on Tuesday, 12 September 2023, it returned 52 results. The same search for “restorative schools” returned 1,210 results whilst a search for “restitution restructuring” returned four results. This implies that there is more peer reviewed research on RP in schools, that it is more mainstream and there is much more to draw from. Therefore, RP has a better foundation for schools to build upon when seeking systems change. In schools where restitution has been implemented, Gossen (1998) asserts that discipline incidents have been reduced - which is consistent with the claims in other similar RJ literature - although O’Connor and Peterson (2013) note that there are no controlled studies of the restitution model in schools; therefore, it does not have the same evidence basis as RP. It is clear that restitution as a model fits under the umbrella of RP. It is primarily a responsive approach to be used after harm has occurred and thus is narrower in range, whereas RP focuses 80 percent on the proactive and 20 percent on the responsive (Wachtel, 2016). Therefore, there is a synergy between these two approaches where restitution can be used to support and benefit both victim and offender, which is the overarching aim of RJ.

Implications

International schools have an obligation towards their unique demographic of students known in the literature as Third Culture Kids (TCK). TCK are a recent phenomenon describing children who live outside of their passport countries often as the result of a parents’ work contracts. “The Third Culture Kid frequently builds relationships to all of the cultures, whilst not having ownership in any” (Van Reken & Pollock, 2009, p. 13). Their lived experience is dynamic, transient, mobile, and constantly shifting but with this comes a range of bespoke social and emotional issues with regards to identity and belonging.

TCK experience a large number of “separations” during their developmental years (Pollock & Van Reken, 2001, p. 166). Ebbeck and Reus (2022) conclude from this that as a result, familial relationships are of heightened importance. For TCK, identity and belonging are about people and relationships (Moore & Barker, 2012, as cited in Donohue, 2022). Therefore, international schools should be cultivating school cultures that promote relationships above all else and RP has a vital role to play in filling this gap and meeting these needs.

As globally mobile children, TCK experience varying degrees of loss throughout their lifetimes and these emotional needs are often underestimated and overlooked (Ebbeck & Reus, 2022). TCK face saying “goodbye” on a regular basis and life can feel like it is in a perpetual state of flux. The experience of losing lifelong friends produces “unresolved grief” (Pollock & Van Reken, 2001, p. 165). With such losses, there is no recognized way to mourn.

Linto (2015) has identified that international school students desire teachers who build meaningful relationships and are highly engaged. Linton states that the “best” teachers are those that are skilled at building respectful and meaningful relationships both in and out of the classroom. It cannot be assumed that new teachers have been trained to build meaningful and respectful relationships with students - especially given they are recruited from countries around the world.

It is important that we understand the relationship between RP and consequences in order to be proactive in addressing pushback from teachers who may be critical about RP as the “soft option” or a “slap on the wrist,” which Clinton (2019) identifies as a main obstacle to RP “buy in.” Gregory and Evans (2020) indicate that up to 20 percent of teachers feel RP does not hold students sufficiently accountable for misconduct and school leaders did not offer enough support to staff struggling with behavior issues. McCluskey et al. (2011) also report serious doubts from staff about RP being used in complex situations as it was seen to be a soft option that blurred the boundaries of what acceptable behavior should be. This misconception holds that RP can lead to a decline in behavior and does not adequately bring accountability for wrongdoing. When RP is implemented poorly, this can unfortunately be true. For this reason, having sophisticated RP policies that are abundantly clear on what the “with” quadrant of the Social Discipline Window should look like in practice (Wachtel, 2016) are essential. Policies that articulate what to do when a student is either not engaging in good faith with a restorative process or perhaps cannot adequately identify how to “make things right” are imperative in responding to this criticism. As alluded to in this paper, this is where the synergy between RP and logical consequences comes to the fore. An underdeveloped understanding and poorly led attempt to apply RP principles can do more harm than good when it comes to misconceptions being confirmed.

If the reputation of RP is damaged as a result of poor implementation, lack of understanding or fear of not appearing to be restorative, then the likelihood of RP being rejected in favor of traditional methods is increased. Detailed and comprehensive policies that map out fine details remove ambiguity and address concerns that practitioners may have. Policies that speak of RP in general terms without troubleshooting the various classroom situations that occur, risk frustrating teachers or planting doubts around the limitations of RP.

Clinton (2019), in her research, identifies that many teachers are afraid that their strength and power is being stolen. Therefore, it is imperative that teachers are listened to, and their unmet needs are addressed. This may be presenting them with a body of evidence to reassure them of RPs efficacy. Or it may be allowing them to engage in restorative processes for themselves so they can experience what it is like to be handled restoratively. Either way, addressing such needs are vital if RP is to be embraced at the systems level.

Many teachers prefer to listen to other teachers, not the researchers (Vincent et al., 2021). If teacher testimonials carry more credibility than university researchers, then key implications that arise here include addressing both how to involve education practitioners in the delivery of positive discipline training - be it RP, RC, or Restitution.

International school teachers come from all over the world and each nation has its own educational systems and unique culture. Clinton (2019) highlights that punitive justice policies are typically mirrored in the organization and management of educational systems. Countries that are tough on crime are also tough on discipline in schools. A unique challenge faced by international schools who embrace Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEIJ) policies is to ensure that all staff “buy in” to the positive discipline approach that is embraced. Considering the vast array of cultural backgrounds and engrained expectations of approaches to behavior, this challenge can only be overcome by explicit training and clearly outlined policies and expectations that are embedded into the systems of the school.

Conclusion

I have explored the synergy between three positive discipline approaches - Restorative Practices, Responsive Classroom, and Restitution. Restorative Practices has been shown to be the broadest in terms of scope and application, providing a framework for aspects of other approaches to be incorporated as well as a rich body of literature drawing from several academic disciplines to support its efficacy in schools. Criticisms have been identified and insights have been offered into creating credible responses and solutions. Logical consequences should play a critical role in school behavior policies, but they must be used primarily through the restorative lens of working “with” students in offering high levels of support as well as high levels of accountability. The purpose and function of logical consequences should always be accountability and never be punitive in intent. It is important that we know this as we seek to build effective policies that work in practice and protect the integrity of our school values and methods. In the international context, the unique social and emotional needs of TCK can be met through whole school systems change informed by a multi-tiered approach to behavior informed by elements of all three positive discipline approaches, with the recommendation that the framework for Restorative Practices is adopted for K-12 schools seeking evidence-based approaches to change.

References

About Responsive Classroom. (2023). Responsive Classroom. https://www.responsiveclassroom.org/about/

Amendola, M., & Oliver, R. (2010). Aggression Replacement Training® Stands the Test of Time. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 19(Summer), 47–50.

Augustine, C. H., Engberg, J., Grimm, G. E., Lee, E., Wang, E., Christianson, K., & Joseph, A. A. (2018). Restorative practices help reduce student suspensions. https://doi.org/10.7249/rb1005

Caldera, A., Whitaker, M. C., & Popova, D. (2019). Classroom management in urban schools: proposing a course framework. Teaching Education, 31(3), 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2018.1561663

Charney, R. (1992). Teaching children to care: Management in the responsive classroom. Greenfield, MA: Northeast Foundation for Children.

Conway, K. (2023, May 1). Five discipline Strategies that Preserve Dignity. Responsive Classroom. Retrieved September 9, 2023, from https://www.responsiveclassroom.org/five-discipline-strategies-that-preserve-dignity/

Costello, B., Wachtel, J., & Wachtel, T. (2009). The Restorative Practices Handbook: For Teachers, Disciplinarians and Administrators. International Institute for Restorative Practices.

Fields, B. A. (2003). Restitution and restorative justice in juvenile justice and school discipline. Youth Studies Australia, 22(4), 44. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=818178860885200;res=IELHSS;type=pdf

Glasser, W. (1999). Choice theory: A New Psychology of Personal Freedom. Harper Perennial.

Gossen, D. (1998). Restitution: Restructuring School Discipline. Educational Horizons, 76(4), 182–188. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42926894

Nelsen, J. (2006). Positive discipline (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Ballantine.

O’Connor, A., & Peterson, R. (2013). Restitution: Strategy Brief. In University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Retrieved September 9, 2023, from https://k12engagement.unl.edu/Briefs/Restitution/Restitution%2011-25-2013.pdf

Philosophy and methods. (2022, May 31). The Experiential School of Greensboro. https://theexperientialschoolgso.wordpress.com/about/philosophy-and-methods/

Renihan, F. I., & Renihan, P. J. (1995). Responsive High Schools: Structuring Success for the At-Risk Student. The High School Journal, 79(1), 1–13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40364737

Responsive Classroom. (2015, January 7). What is Responsive Classroom? [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved September 9, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mhV6AcBxeBc

Responsive Classroom. (2015b, April 27). Our approach (Overview: Part 1 of 2) 2015 [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved September 9, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-bPL8YiqAwo

Wells, L. (2022, September 2). Four powerful ways you can shift your teacher language to welcome students | Responsive Classroom. Responsive Classroom. Retrieved September 10, 2023, from https://www.responsiveclassroom.org/four-powerful-ways-you-can-shift-your-teacher-language-to-welcome-students/

What is MTSS? (n.d.). Branching Minds. Retrieved September 12, 2023, from https://www.branchingminds.com/mtss-guide

--------------------------------------------------------------

Alistair is the founder of Restorative360 and is a passionate advocate for restorative practices in education. A graduate of both Glasgow and Strathclyde Universities, Alistair teaches social sciences, International Baccalaureate global politics, and Theory of Knowledge, and is a grade-level leader the International School of Kenya. Prior, he taught history and was the theory of knowledge coordinator for nine years at the British International School of Jeddah.