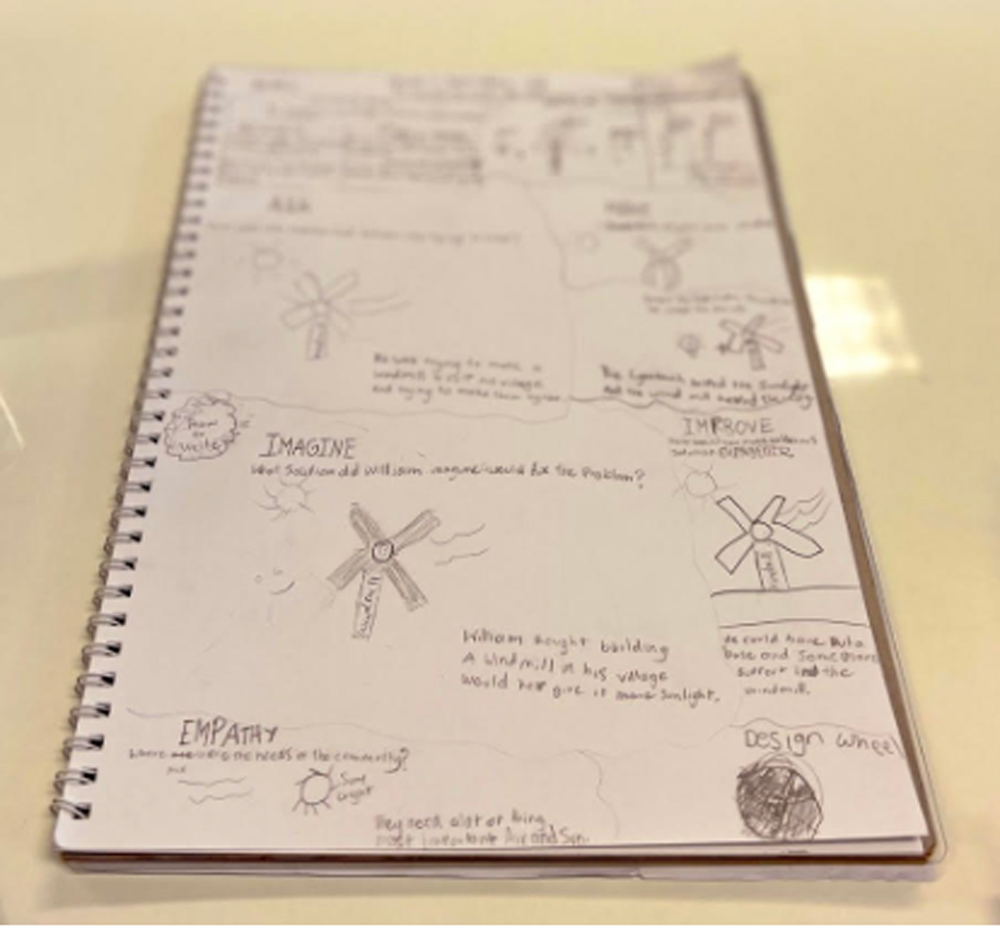

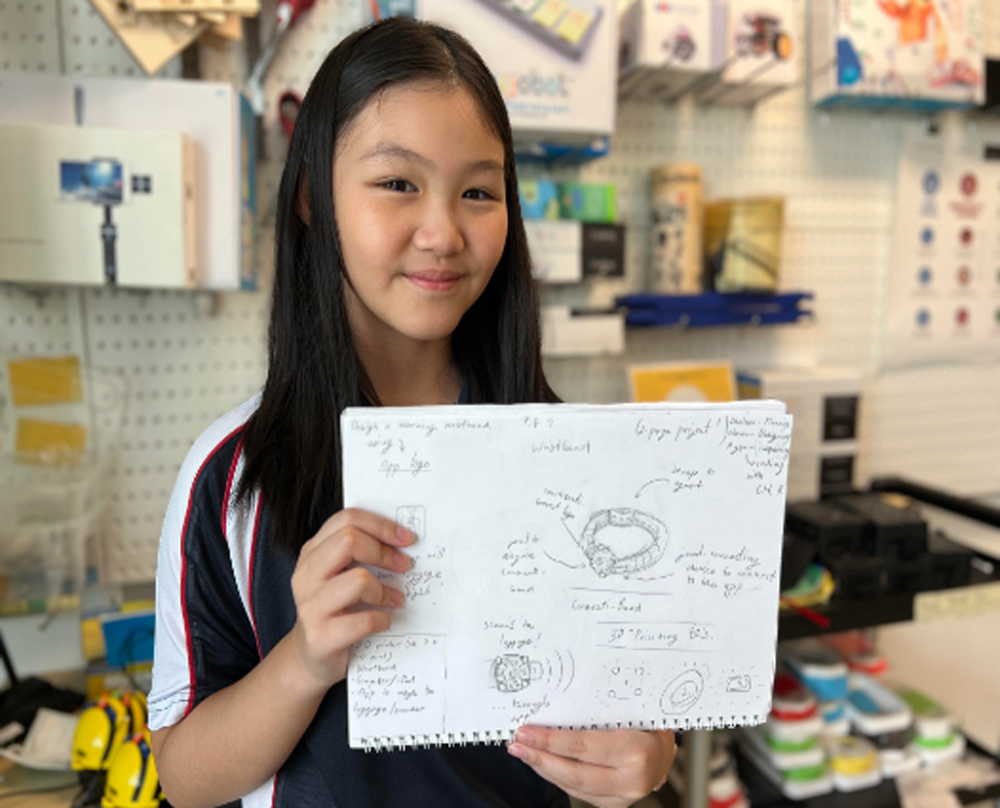

Stamford American International School's approach to the Design Cycle. (Photo source: Aisha Kristiansen)

--------------------------------------------------------------

“Schools are facing increasing demands to prepare students for rapid economic, environmental and social changes, for jobs that have not yet been created, for technologies that have not yet been invented, and to solve social problems that have not yet been anticipated…”

The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030,

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

What will the future of work look like in five, 10, or even 15 years' time? What skills need to be taught to equip future generations with the proficiencies required to solve the challenges that lay ahead?

The Case for Design Thinking in the Primary Years Program (PYP)

The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030 OECD report states that the ability to navigate through a “complex and uncertain world” will be paramount for the next generation of learners. Climate change, rapid technological advances, global health pandemics, and increasing inequality are just a few of the problems that will demand a unique set of problem-solving skills from our students. The OECD report also acknowledges that schools are responsible for providing the conditions for learner agency, finding explicit opportunities for them to influence their future and act on injustice. In fact, the report highlights that schools have a moral imperative to develop a “broad set of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values in action” so that our learners can become the change agents of the future.

With this in mind, Stamford American International School Singapore identified the need to intentionally plan a unit of work for each grade level that specifically addressed design thinking and real-world problem-solving. As a school, we also wanted to promote a culture of innovation, both for our students and our staff. Author Everett M. Rogers defines innovation as “a new or modified practice and/or technology that supports any part of the education ecosystem and leads to meaningful improvements in a given context.” Meaningful improvement being defined as having evidence over and above what already exists for the intended users. The new design cycle needed to guarantee “meaningful improvement” for our students through increased student agency, creative problem-solving, and new ways of thinking about real-world issues.

The Elementary School Design Cycle

When creating the Elementary Design Cycle, we needed to consider the work being done in the International Baccalaureate’s middle years program (MYP). The Design Cycle utilizes a similar framework for the various stages of design thinking. Terminology consistent with the MYP and complementary visual layout were also important considerations. Developing a sense of empathy in our students was a key criteria, as was the ongoing process of research, documentation, and feedback. Visuals were also added to support our learners. The new Design Cycle was built into our approach to inquiry learning created by our PYP coordinator, Michael Hughes. The three stages of our approach to inquiry include “Finding Out,” “Making Connections,” and “Going Further,” with “Tuning In” happening at the commencement of each stage.

Once created, the new Design Cycle was piloted with the Grade 4 team during the “Where We Are in Place and Time” unit. The central idea, according to Hughes, was that "knowledge, resources, and circumstances contribute to innovation and advancement.” Initial observations from the teachers about the new framework included the importance of having a shared language, the systematic way that students could name and notice the various stages, the opportunity for critical thinking, and the detailed documenting and monitoring of student learning. Student engagement was high, as was the ability to utilize their creativity and problem-solving skills.

During the “Finding Out” stage, the students unpacked a case study about The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, a book about a Malawian boy named William Kamkwamba who created a windmill from locally sourced materials within his community. They began to understand that innovation springs from knowledge, resources, and circumstances. The students then used the “Making Connections” phase to uncover opportunities to innovate in their own lives.

Developing Changemakers and Problem-Solvers

The Design Cycle steered students to work through a process in order to become real-world changemakers and problem-solvers. The true evidence of impact lay in the “Going Further” stage of the inquiry where learners were challenged to reflect on a problem in the world that they would like to solve. The vast array of solutions to the various issues demonstrated the students’ ability to be active and engaged and empowered participants in the learning process when the intended space and structure were carved out within the curriculum.

In parallel to the pilot, curriculum mapping across the grade levels ensured that the Design Cycle was strategically embedded into the yearly overview. From envisaging disaster-proof housing to creating a device that would communicate light and/or sound, students used their ingenuity, innovation, and design thinking skills to achieve meaningful improvements in their learning.

Using Empathy To Build a Fair and Just Future

At the heart of this work was the notion of developing empathy in our learners by using design thinking. According to An Introduction to Design Thinking PROCESS GUIDE, design thinking starts with the premise that “to create meaningful innovations, you need to know your users and care about their lives.” By encouraging our students to work through solution-focused problems that kept the user at the heart of the work, we were able to build empathy, understanding, and compassion. These are some of the most important human characteristics if we are to build a fair and just world for future generations and achieve the OECD’s objective of creating an equitable education system for all. Imagine a world that considered the impact of decision-making on key stakeholders. Now that would be a world worth designing!

Introducing design thinking into our school context for our PYP students has been a game-changer. It has challenged our students to become proactive problem-solvers and real-world changemakers. The Design Cycle has added meaningful improvements to our students’ learning and allowed our teachers to build a culture of innovation and action. If you would like to find out more about introducing design thinking into your international school setting or any of the projects mentioned here, please feel free to connect through social media.

References

Green, Crystal and Ziegler (2023), “Implement at Scale: An Agenda for Education Innovation Implementation Research”, https://hundred.org/en/articles/an-agenda-for-education-innovation-implementation-research(accessed 27th May, 2023).

OECD (2018), “The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030”, https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/about/documents/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf (accessed 28th May, 2023).

Institute of Design Stanford, “An Introduction to Design Thinking PROCESS GUIDE”, https://web.stanford.edu/~mshanks/MichaelShanks/files/509554.pdf, (accessed 12th May, 2023),

--------------------------------------------------------------

Aisha is the digital learning leader at Stamford American International School in Singapore.

Twitter: @Aishakrist

LinkedIn: Aisha Kristiansen