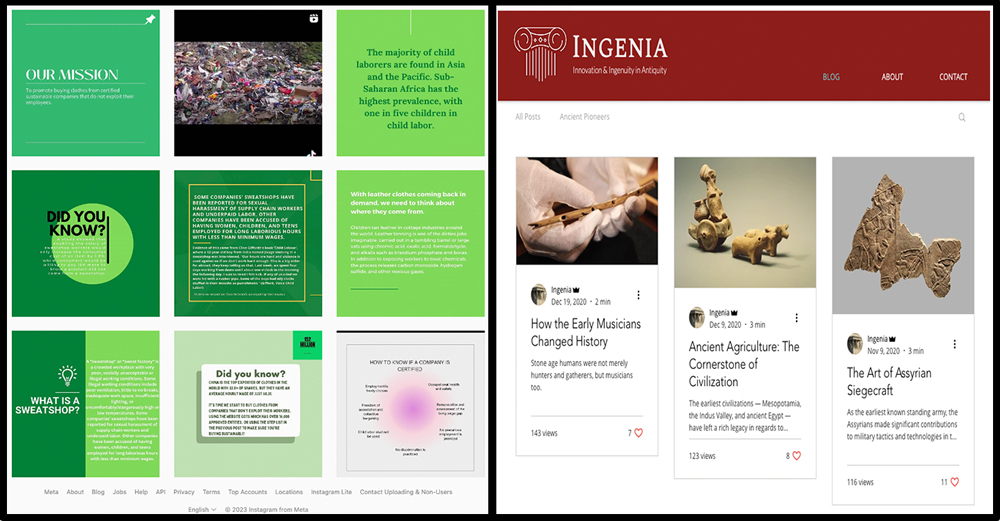

(From left to right) A project designed to provide wellness information to our staff, a lost-and-found program focusing on using technology to identify the owner, and a prototype of a shade for a bike sharing program in Dubai. (Photo source: Laurence Myers)

--------------------------------------------------------------

Setting the Stage

By now, most of us have been told that we need to move from a “sage on the stage” to a “guide on the side” approach to teaching and learning. For several decades, those of us who’ve been in education have witnessed the gradual (though not always fluid) swing toward student-directed learning. Research indicates that students learn best when learning is relevant and engaging to them, and what better way to do that than to allow them a good amount of decision making in the learning process. We’re all, in some way or another, willing to try it out and find our own balance between what we are comfortable controlling and what we are comfortable letting go of as we move in the direction of student-directed learning in various degrees of expediency. The constant ebb and flow of “content” versus “process,” the balance between the proverbial “science” of teaching constantly mixing in with the “art” of teaching and learning.

As tangible examples are still rather limited, it is sometimes difficult to recognize what it might look like. Enter the age of trying new things and transparency as a means of collective efficacy in doing just that. At the American School of Dubai, we combined a number of independent, research-based projects to create a common approach to self-directed learning. Not quite a research project (though it could be) and not entirely an open-ended learning experience (though there are elements of it), the Self Directed Project (SDP) was created during the height of COVID, in part to address the limitations we had with face-to-face learning, but also to celebrate the fact that learning looks different from one student to the next!

What is the SDP?

The Self Directed Project is an elective course offered to Grade 10-12 students at the American School of Dubai (a United States curriculum school). Its course description highlights the fact that it’s student-directed and that it will result in an outcome of the students’ choice, but there is much more to this than might initially meet the eye. When participating, it doesn’t take students too long to recognize that this is a “process-based course” and that the advisor is not (necessarily) a content expert. Though the topics covered are individualized, the process is similar for everyone. So, what exactly are the essential elements of the Self Directed Project? In short, the learning:

What is the role of the advisor?

One of the best things (for those comfortable with ambiguity anyway) is the fact that on day one of the course the advisor/teacher walks into the room with zero knowledge of what it is that this course will “look like” for each student. That is to say, there is no starting point in terms of content. The beauty, perhaps, is that the course’s process allows ample opportunity for students to develop their personal journeys within the confines of their personal interest, skills, experience and/or concern.

Much like instructional coaches support the process of student learning through what commonly looks like a “coaching cycle,” the work of the advisor and student are oriented toward the needs of the student. Lots of questions are involved, of course:

These questions might be heard throughout the semester as the student moves from one part of the process to another. For some students, especially those with a very focused idea of their topic/interest, this might mean trying to expand the learning journey just a bit to allow students to see themselves as action-takers within their community. In other cases, those where students have a wide array of possible foci, the role is to support the process of identifying what the learning journey might look like based on the true “why” of the student learning journey.

Regardless of the starting point, the advisor/teacher’s role is that of a learning guide, a questioner, an experience-sharer, and a resource. The largest value an educator can provide is to ensure that the student’s learning is well planned out by the student, that the timeline is balanced enough to allow for “deep dives” and support movement when a student might become entrenched in that space of “analysis paralysis.” In fact, this distinction is what most sets this course apart from more traditionally structured ones. In the SDP students take their analysis and act on it, testing their own assumptions and ability to make authentic change. This is quite different from traditional courses where engagement is limited to within the classroom itself (e.g., an in-class presentation, a research paper seen only by a teacher, etc.). The informed action step of the SDP is, of course, one that students might need particular support in, both in execution and in the manner by which to assess its impact.

What does SDP learning look like?

The learning utilizes a lot of flexibility, but not without a predetermined process (identified above). Students and their advisor work independently in many ways since it is, after all, a largely independent project though, by design, could be collaborative as well. Students have check-ins with their advisor each day that the course is scheduled for ongoing connection and potential pivoting, if necessary.

The learning begins with open ended questions about the students themselves (social-emotional learning anyone?), speaking often about passions, likes, dislikes, learning approaches, etc. In recognizing the student and what they bring before the course even begins, the advisor is able to get a preliminary picture of the context of the student as a learner. Once the student-advisor relationship is created, it never ends. But the conversations morph from the students themselves to the things that are important to them.

From here on, we utilize systems thinking tools (we rely a good deal on the Compass Education tools) to both delve deeper into the topic(s) of interest and to generate connections to potential supporting topics, even less obvious ones. These tools are revisited a number of times throughout the learning journey both to add to the conversation (formative) and to make decisions.

From there on, students create guiding questions as well as make connections to the targets of the SDGs. The idea is that most anything they do begins with the recognition that personal investigation and action are often related to the larger picture. We use the SDGs as the context for these “think global, act local” types of conversations and informed action.

The rest of the learning is often all about authentic conversations and utilizing the MISO method (introduced to us by Cathryn Berger Kaye). MISO (media, interview, survey, and observation) are ways of identifying critical information that allows students to move toward answering their initial guiding questions. And here, right here, is where the true student-driven work begins. There is significant skill-building and meaning-making in identifying the appropriate means of gathering data, communicating one’s intent, and making decisions related to one’s inquiry. For example, what is the best approach to address the guiding questions students have generated? How does one gather valid information from a community? What is the best way to observe behaviors and make sense of those observations? How does data lead to a deeper understanding of an issue in such a way so as to identify potential actions to support/address it? This inquiry is the beginning of a personal journey of discovery, reflection, and informed action for students as they recognize the systemic connections and dynamics involved in their topic/issue.

The ebb and flow of learning is often just a cyclical process of check-ins and decisions made by the student(s) with the guidance of the advisor. On occasion, the focus of the project is only identified after several rounds of data-gathering and reflection on that data. Students literally learn as they engage, meaning their learning is defined and redefined as the course progresses. In the process, students use their leverage to make positive change in the world around them, as big or as small as that might be for them. This is a true delight for an advisor who finds value in the shared discovery of learning!

What outcomes are we looking at?

When we talk to students about the outcomes of the course, we discuss the “tight” (i.e., what must be done) and the “loose” (i.e., what is flexible). Informed action is a required part of the course and must be determined after the investigation has been completed. What is also “tight” is that this action needs to be done in an authentic manner.

For purposes of this course, we define “authentic informed action” as outcomes/actions that:

The general guideline we have for students is that they have to “marry” their work with the audience or environment that they want to benefit. For example, a student who is building a model of a bike-share flexible bike shade needed to present it to Careem (a bike-sharing company in Dubai) and receive feedback from the company spokesperson. Similarly, students have created online spaces, published articles, shared research with non-government organizations, developed tools for in-school energy data collection and communication, run local conferences for a number of schools, etc.

The final “outcome” of the learning journey is the SDP Share Out. In this event all student participants are asked to share their learning journey (in its entirety, not simply the final outcome) and reflect on their own journey. They share this information to a broad group of student and adult members of our community. This conversation is intended to create increased accountability (without formal assessment) while allowing the visiting listeners to ask questions and provide ideas for extending the experience (e.g., “Have you thought about doing…?). This is not an assessed element of the course, though it is a mandatory element. Students and visitors always find this element a powerful way to create closure in a semester’s worth of learning.

(From left to right) An SDP student leading a joining working session with students and cleaning staff, producing reusable feminine hygiene products and a student leading a roundtable discussion on sustainability related issues on campus. (Photo source: Laurence Myers)

What about assessment?

I like to think of true learning as a shared conversation with a common goal, growing from doing and reflecting. As such, the assessment of this course has different components to it, largely based on reflection.

At every step (investigation, planning, action, reflections) students self-assess and then, jointly with their advisor, determine an appropriate descriptor for their work. The assessment rubric is utilized as a reflective tool more than an assessment tool but the conversation benefits greatly from the use of the rubric as a “third point.” The rubric categories, with the collaborative assessment results, are reported to parents as assignments to ensure transparency throughout the experience.

Students also engage in self-assessment relating to our school’s Student Profile, which focuses on self-awareness, communication, empathy, innovation, resilience, and global citizenship. For each of these attributes, students utilize the Student Profile to view their own learning from a broader context than simply the content of the course. Regardless of what the topic of their SDP might be, most students inform us, time and time again, that all of these elements benefit from the process of self-directed learning.

Finally, there are the required elements of the course itself, most notably the informed action. We do not require informed action to be successful. Rather, we ask students to identify what success would look like in their view (what we call impact data) prior to their taking the informed action and then, following the informed action, to reflect on the level to which the data indicates success or not. In international education, we often speak to students about failure being a learning experience. In this case though, the presence of action is mandatory, its “success” is not. Once again, it’s the reflective conversation that takes place that leads to the learning, not the level of success one might reach. It helps, though, that most students are quite successful too.

What can educators/schools learn from our experience?

Education is never final, and the way education “looks” can be quite different, sometimes within the same institution. In the spirit of the constant evolution and the growth mindset we all like to speak of, this course was a little bit of all of these. It allowed us to do a few things:

Is the SDP perfect? Far from it. Is it for everyone? Perhaps not. But it is flexible enough to allow for most everyone to find it a useful and powerful learning journey. At the very end of the semester, we ask our student participants to provide a one sentence statement that defines what their “big take away” was. Interestingly, the students themselves, when prompted to reflect on their journey, don’t tend to focus on the content either.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Laurence Myers is the K-12 service-learning coordinator at the American School of Dubai.