“Allow yourself to write poorly.” This is what I told a student one day during after-school tutorials, a sacred time for students to check in with teachers. I rarely have many students attend and when they do it’s usually in regard to an upcoming deadline: a paper or presentation, a thesis statement to sharpen, a discussion point to talk through, or a wobbly body paragraph to align. No judgment there. Students have much to prioritize and balance and English class is simply one of many. This student on this day wanted to talk about creative writing. Specifically, they said they wanted to write a short story but didn’t know where to start. Their comfort with writing, they said, rested in poetry. I said, “Tell me more about that,” because I can’t help myself. For me, the process is as interesting as the product.

Poets are fascinating creatures. How does one take a thing of great personal significance and make it into a tiny nest of words? Prose makes sense (or more sense) to me. You have this running narrative that holds a story together and tells us a little more about a character or two. But, poetry, my goodness! The courage it takes to commit to words with such risk, and care. A prose writer can be a little clumsy; the poet cannot.

In sharing more about the process, the student showed me some of their poetry. Needless to say, I was awestruck. Goosebumps. Brilliant. What in the world could I offer this artist? When it comes to reading, I’m an easy reader, admittedly so. If I read something, I’ll find something in there to like. I can’t help myself. Despite my affinity for the written word, this kid had chops. Stunning words bopped and mingled and serenaded there on the white page, pinching my nerves and shaking my soul.

The student waited then for me to say something. I gave her, “Well, with writing a story, allow yourself to write poorly” (at first anyway).

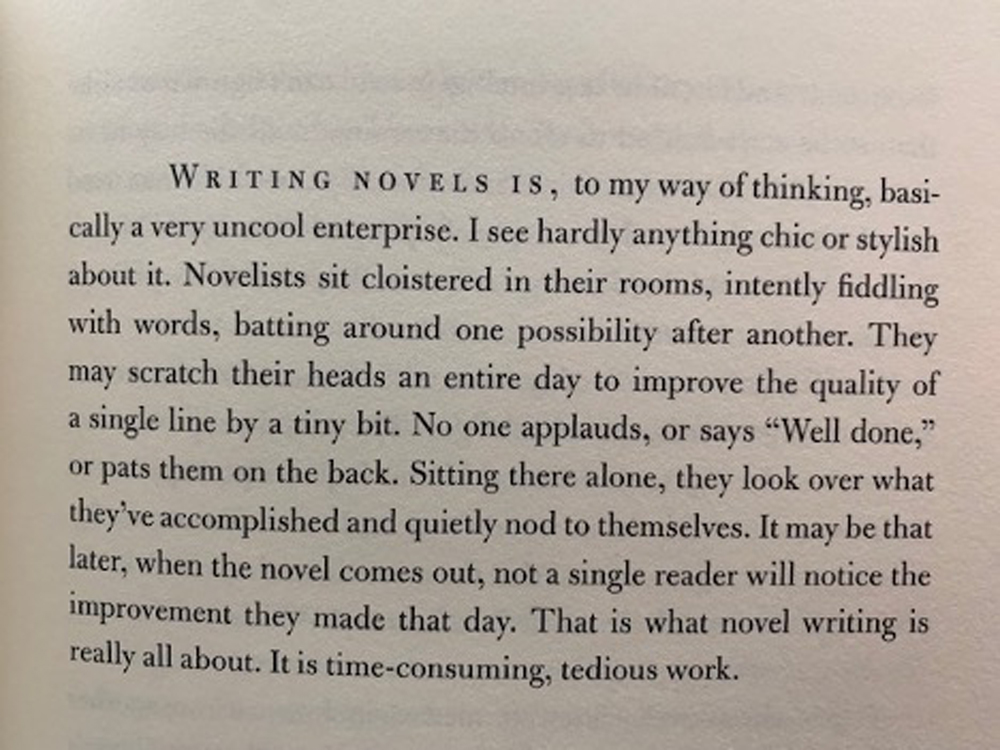

Haruki Murakami’s recent memoir, Novelist as a Vocation, offers intriguing insight and anecdotes about his life as a professional writer. This is certainly not what everyone can or should strive for, or can afford to strive for, and yet Murakami very delicately humanizes the process of writing or rather, his process.

Page 13 of Haruki Murakam’s Novelist as a Vocation. (Photo source: Bradford Philen)

My student may or may not have aspirations to be a professional writer, though that is not the matter in this excerpt, I don’t think. It’s the solitude, the time, the perseverance to sit with a line or a paragraph when one sets out to write. There are a million things to do in the world and sitting with a sentence isn’t necessarily one. And yet, there is clairvoyance in sitting with a draft, in sitting with a rewrite (and another and another). This, I think, is all true and at the heart of what Murakami means. The writing evolves, the story, the characters, the possibilities. Oh, yes, the possibility of words! This is sort of what I mean when I tell my student to “allow yourself to write poorly.”

Another, perhaps more poignant, passage from Murakami explores how he has learned to follow a story. In reflecting on his writing of Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, he writes, “…in almost an instant, the words that Sara spoke completely changed the story’s direction, character, scope, and structure. This was a complete surprise to me…So Sara was, again, perhaps a reflection of my alter ego, one aspect of my consciousness telling me not to stop at the place where I’d intended” (pg. 164). This is an interesting process and one that many writers, I imagine, utilize in their day-to-day practice. You have an idea, a character, a place, and as you engage with and water that seed, it grows, and you are the root for the branches of the story that go every which way and burgeon flowers and fruit and hopefully invite the wandering bee to pollinate and make honey. Or something like that. In short, the writer is merely a vessel.

At work, a friend and I marvel at another writer, Walter Mosley. While Murakami’s next and newest novel is set to hit bookstores in April of this year, Mosley is, perhaps, even more prolific (though this is no race that’s for sure). Said friend was reading one of Mosley’s many crime fiction books while I took to The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey. Such a compelling story. Another friend and colleague within our corridor has read every Atwood book. I wonder what English class was for Murakami, Mosley, and Atwood in their day. Murakami does take some pages to reflect on his high school experiences and notes how he was an avid reader though not as driven academically as his peers. Moreover, I wonder what these literary giants would suggest for English class today, for school for that matter.

For better or for worse, hallway chatter amongst colleagues has centered around the (somewhat) recent ChatGPT. I recall reading this article back in November and even then I thought, “Well, here this is, which really means we are already several months behind.” This is a chase that we (teachers) will never win, and writers too perhaps. The product will trump the process, and I use that verb with great trepidation. The world wants the product to trump the process.

Hasn’t there always been a need, or want, or energy, to escape the process for the product? Personally (and philosophically and pedagogically), I like this article much better, What Poets Know That ChatGPT Doesn’t. One of the key sentences from writer Walt Hunter is, “Creativity requires more than an internet-size syllabus or a lesson in syllables.”

Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s work is raw and hits me and my students upside our collective heads. She writes about the natural world (My Cephalopod Year) as much as she does about identity and parents (Mosquitos) and growing up (After Challenging Jennifer Lee To A Fight) and Hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia. Here are a few lines of that poem, “coal lung. Be afraid of money spiders tiptoeing / across your face while you sleep on a sweet, fat couch. / But don’t be afraid of me, my last name, what language / I speak or what accent dulls itself on my molars” (pg. 49). She has an immense range of thinking in her words, and I would argue that her writing is a testament to the idea that with conviction, purpose, and process, there’s nothing you can’t explore with words.

With my student, I have an imagined conversation swirling in my mind and in that scene I will ask, “What’s the writing for?”

“What do you mean?” they say.

“I mean, this writing you’re doing, the short story, what’s it for?”

“I don’t get it.”

“I mean, there’s no test. This isn’t to be turned in for a grade. You’re here in tutorials, chipping away at a story and you’re a damn good poet. What’s the writing for?”

They give me a blank look. As if I am from another planet. And then they open their mouth and words soar into the ether like the flapping of hummingbird wings. “I am writing to find my heart, to find what’s real and what makes me me!”

This is the song to yell to the heavens and the seas and the mighty ancestors of the world who believed in words rather than assessments.

“Oh, of course,” I say, for I am not a poet, not like they.

If we are going to scrutinize and obsess over artificial intelligence and the integrity of assessments, then so be it. These lines were drawn long ago. The least we could do is spend as much time and energy on the creative process, which is the real product.

References:

Hunter, Walt. “What Poets Know that ChatGPT Doesn’t.” The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2023/02/chatgpt-ai-technology-writing-poetry/673035/. Accessed 15 February 2023.

Murakami, Haruki. Novelist as a Vocation. Translated by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen, Knopf, 2022.

Nezhukumatathil, Aimee. At the Drive-In Volcano. Tupelo Press, 2007.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Bradford Philen teaches high school English in the Philippines, where he lives with his wife and kids. His fourth book, a novel, is forthcoming in 2024 with Tailwinds Press.