As educators, we make decisions every day as we plan our classes. The choice of activities, the approaches we take to deliver the content and maximize students’ learning, our responses to our students, our tone, mood as well as the home and school experiences of the students can all be triggers for behaviorism and behavior management.

What are the different ways and approaches that we can take as educators to train students who can think critically, construct their own meaning, take risks, and make sense of the world around them?

There is a difference between teaching students a concept and lecturing them about a concept. I argue that teaching a concept is sharing knowledge with students that they need to have to meet whatever goals or objectives set for them. How they maneuver, explore that new knowledge, and construct their own understanding should not be restricted by the teacher’s own vision and expectations. Instead, guidance and coaching are offered to students. Lecturing about a concept, on the other hand, is telling students how to approach the new concept, how to think about it, and what to do with it, all within the vision and expectations of the teacher.

If we think about ourselves as adults, we often don't respond well to those who are lecturing us or telling us what to do. Just like students, depending on the power dynamic, we listen, do as we're told, and move on and pretty much forget about the lecturer the minute we leave the interaction or the situation. On the other hand, if the individual is not lecturing us, but is instead sharing with us their wisdom, experiences, and expertise in a way that is empowering, inclusive, and invites the participants to get involved and inquisitive, we respond positively.

Learning is empowering while lecturing leaves little room for inclusion, reflection, critical thinking, or the opportunity to thrive.

Some may argue that we cannot make learning empowering all the time. It might be possible in some subjects and difficult in other subjects and we cannot keep things interesting all the time. I argue that the objective should not be centered on making the content interesting, but instead, building momentum within the content that helps students find relevance in it.

Neuroscience tells us that learning is stronger when it matters (Peter C. et al, 2014). It is when our brain makes associations with prior knowledge and makes a sense of connection with new knowledge that durable retention happens and thereafter grows the capacity to carry the cognitive load (McGraw-Hill, 2019). But what happens when what students see, read, and learn is foreign to their world and experiences, and when their identities and view of the world are not represented in the classroom? How are they going to level up their cognition in the same way as those whose world and identities are represented in the classroom and school?

Meaningful learning happens when students can connect what they learn to who they are. As educators, if we consider the different ethnicities and identities of our students as we are making pedagogical choices and start by using the wealth of knowledge of our students’ community as Teddi Beam Conroy, associate professor at the University of Washington argues, we will “prioritise students’ growth and create spaces that affirm their identities” (Education Week, 2022). According to Professor Gloria Ladson-Billing, a culturally responsive teaching approach aims at understanding students’ cultural identities, creates an environment where diverse perspectives are offered, and embraces as well as honors the different communication styles to empower all students to become critical learners (Education Week, 2022). Django Paris argues that we also need a culturally sustaining pedagogy where multilingualism is celebrated, and whiteness is not centered in the classroom so that knowledge of marginalized communities can also inform teaching. This way, we can increase all students’ cognition as we offer instructions that allow them to make associations and ultimately create a sense of connection.

It has happened many times with my French or English as an Additional Language (EAL) students who learn new vocabulary, use them in class, do the quiz, get a high score, move on, and forget all about it. The week or two after when the same words are mentioned, students look at you as if it is the first time. They hear the word and you might hear, “I know what it is - it’s when - it’s like - I know what it is but I don’t know how to explain.” Rehearse and Remember Rote learning are behaviorist methods that give the impression of learning as it is effective on a short-term basis. Brown et al. argue that “rereading and massed practice give rise to feelings of fluency that are taken to be signs of mastery, but for true mastery or durability, these strategies are largely a waste of time” (2014:3). So, how do we create an environment for students beyond rereading and massed practice where they continuously use the new vocabulary in different contexts and retrieve them as often as possible?

In my former EAL Year 8 class, I challenged students to learn 10 to 15 new words each week for the end of the week vocabulary quiz. They were allowed to use paper dictionaries (English to English) available in the classroom. They were also invited to use bilingual dictionaries from their first or preferred language as long as they were aware that some words can have a different meaning in English. A good example is the English word sensible. It is spelled the same way in French but has a different meaning.

Letting them use dictionaries in a vocabulary test helped them to understand that just because you know what a word means doesn’t necessarily mean you can use it in a sentence. I also wanted them to see for themselves the importance of understanding the different parts of speech. Why are adjectives, nouns, adverbs, and verbs important to understand? Why are we spending time working on it and how relevant are they to them as language learners? Until students can see the relevance themselves, they will not understand the point of learning grammar and will not intrinsically be motivated to learn and grasp the concept.

The test was a fill in the blank task. They needed to choose from 17 given words but only 15 words could be used. They grabbed their dictionaries, looked up the word, and started filling in the blanks. As they did, they realized that some words did not work because they did “not feel right.” This was the moment they were reminded that knowing the definition is not enough to complete the work. They also should remember that if there are articles before the blank, they should look for a noun. Knowing that a sentence must have a verb, which comes after the subject, which requires them to understand word order (subject, verb, and object) is important. If a noun is being described, they should look for an adjective and if an action is being described, they know they’re looking for an adverb.

The faces looked more confused. Looking up the word in a monolingual and/or bilingual dictionary, and for some, looking up what the word meant in their first language, identifying the different parts of speech, reading and understanding the meaning of the sentence to be able to find the appropriate missing words required some cognitive effort. At this point, the students were doing retrieval and elaboration1 practices at the same time.

What was thought to be a quiz that should have lasted 15 min was now taking up double the time because the students were engaged in deep learning. It was not as easy as they thought it would be, but they were doing important work because “when learning is harder, it’s stronger and lasts longer” (Brown et al., 2014).

At the end of the quiz, one student said, “I knew there was a catch. You can’t just let us use dictionaries - you knew it was going to be hard.” And another said, “It didn’t feel like English. I felt like I was doing something else - I had to think of many things.”

The week after, they had the same test with ten more words to learn plus the last ten they had before, and we did this for five weeks. The testing was not made to measure learning but to enhance learning. Testing was an opportunity for students to retrieve knowledge and recycling the words allowed spacing and interleaving to happen, which “leads to stronger long-term retention than when it is massed” (Brown et al., 2014). I was pleasantly surprised when I heard my students use the vocabulary in class during classroom discussions. The new words had become part of their functional vocabulary repertoire.

One could argue and ask what the point is of having a vocabulary quiz if students can look up the word. They need to know the words as they will not always have a dictionary! And this is exactly why I opted to use this method because they will not always have a dictionary indeed. After five weeks, the students wrote their essays with fewer grammar errors and used the new vocabulary without needing a dictionary because retrieval practices from memory are a great tool for learning and durable retention.

Such results never happened through the rote learning method because “while cramming can produce better scores on an immediate exam, the advantage quickly fades because there’s much greater forgetting after rereading than retrieval practice. The benefits of retrieval practice are long-term” (Brown et al., 2014).

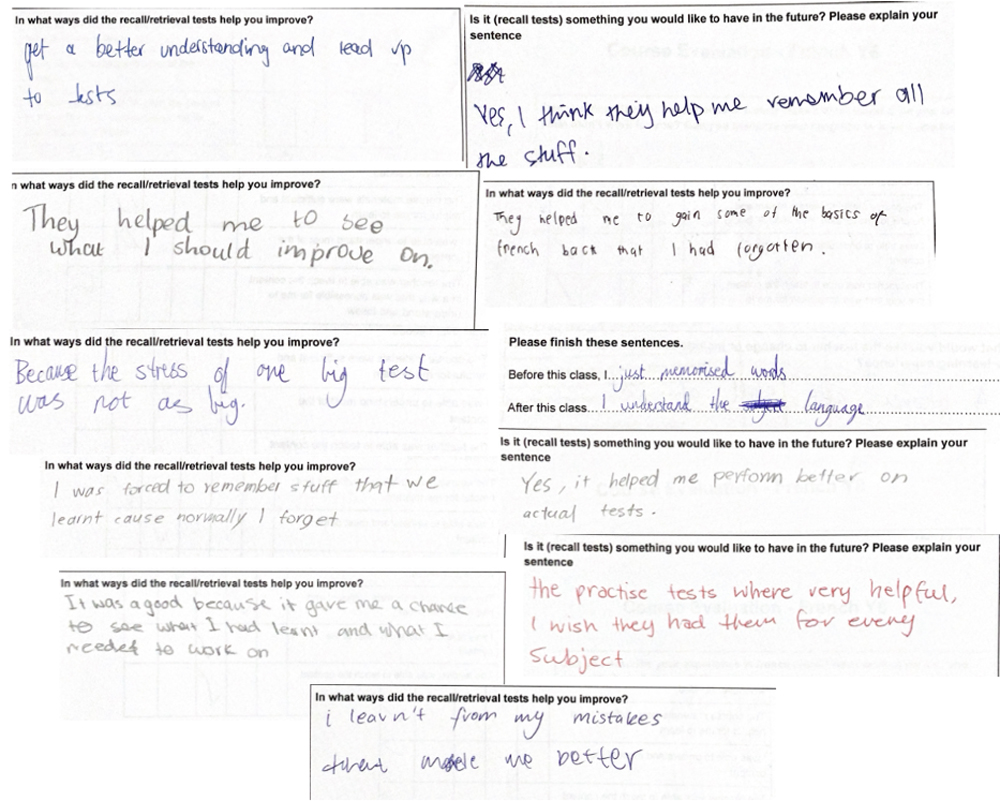

The same benefits can also be seen with my former French Year 8 students in Melbourne who have little exposure to the French language and who struggled to understand the language and its mechanism as seen in their previous assessment scores. The weekly recall tests, whether it was immediately after new knowledge was introduced or a few days later, proved durable retention and better scores in the end of term exams. All students improved their academic performance and more importantly, they started understanding the language as opposed to memorizing content as they describe below and enjoyed learning the language.

Student feedback and reflections. (Photo source: Doline Ndorimana)

As we choose content and plan our lessons, it might be worth asking ourselves:

For example, if the learning objective is limited to “students learn how to talk about hobbies in French,” it is unlikely to generate a discussion other than this is how you say it in French. However, if the learning objective is understanding “the importance of sport and leisure for our personal wellbeing and that of others” it will likely generate and open a discussion. Learning how to express hobbies should be a vehicle to a bigger purpose.

Creating space and affirming environments where students can connect what they learn to who they are, construct their own meaning, share power with them, and recognize that as educators we can also learn and grow from the wealth and knowledge of our students’ community can make meaningful learning happen. The learning that goes beyond the classroom, shapes students’ minds and growth into becoming better versions of themselves.

References:

[1] The process of giving new material meaning by expressing it in your own words and connecting it with what you already know (Brown et al., 2014)

--------------------------------------------------------------

Born and raised in Burundi, Doline Ndorimana is an international educator, DEIJ workshop leader, and university lecturer with 15 years of experience in international schools. She is also a language acquisition middle years program consultant, part of the TIE editorial committee, and a member of the Association for International Educators and Leaders of Color (AIELOC) and the International School Services (ISS) Diversity Collaborative. Doline is trained in international accreditation as a team evaluator and has been involved in accreditation visits. She is a great advocate of students’ voices and works at amplifying them by helping to create a culture of inclusion and vulnerability in schools. She now lives in Melbourne with her family.

Twitter: @DolineNdorimana