This article explores the ethical complexities of teacher use of generative AI and offers concrete steps to navigate them. You’ll come away with:

Innovation… and Controversy

Your school leader instincts are as sharp as the Terminator’s targeting system—constantly scanning, zooming, and processing what’s happening in the learning environment. You’re masterful at zeroing in on high impact learning at your school, and quick to spotlight examples of excellence. This week, a Grade 5 teacher designed an innovative learning experience that will captivate students and spark genuine engagement. Her “Design a Roller Coaster” unit expertly incorporated math, physics, hands-on experimentation, peer collaboration, art and design, and core economic principles. It also empowered students via choice, authentic learning tasks, and multiple ways to demonstrate their understanding and skills. What’s not to love?

Eager to celebrate her work and inspire others, you decided to spotlight the unit at a faculty meeting. Colleagues were both impressed and intrigued. When they asked how she created such a dynamic and engaging learning experience, the teacher beamed and replied, “ChatGPT® made it easy!”

Suddenly, many faculty members’ congratulatory smiles shifted to raised eyebrows, genuine curiosity, and quiet disapproval. Though quite a few colleagues nodded admiringly, one particularly professorial teacher gasped audibly and placed her hand on her chest. You started to feel like the Terminator again, only this time it was because it seemed the future of the world–or at least the immediate future of AI use by teachers in your school–depended on what you do next. The complex and pressing question filling the silent air is: What are the ethical implications of educators using artificial intelligence (AI) in their work?

Mixed Messages: Teachers, Students, and the Ethics of AI

Similar scenarios are likely unfolding at your school or district. The use of AI in the learning environment can provoke strong, sometimes polarizing, reactions among faculty members. Recent studies reveal a significant divide in teachers’ perspectives on AI’s role in education. Proponents emphasize the many ways AI reduces the time teachers spend on tedious tasks, allowing for more meaningful engagement with students. At the same time, a 2024 Pew Research study found that 25% of public school teachers believe that AI tools do more harm than good in the K-12 setting. Meanwhile, a 2025 Education Week poll revealed that 60% of the 1,186 teacher respondents had integrated AI into their lesson planning, while 39% had not. Students also have strong and varied opinions about teacher use of AI, especially for grading. In a December 2024 article, The New York Times highlighted student concerns around fairness and the impact of AI on the student-teacher relationship. While some appreciated the efficiency and timely feedback AI can provide, others felt the practice “devalued the student-teacher relationship” and “undermined integrity.” These perceptions raise important ethical considerations about AI’s place in the classroom.

Similarly, a May 2025 article in the Farmingdale Observer suggested that some tertiary educators are drawing criticism from students for “overusing” AI. The article refers to student disillusionment being expressed on platforms such as Rate My Professors, where students have complained about cliched slide decks, impersonal and imprecise feedback, and even some incoherent responses. Similar to universities, the families of international school students pay tens of thousands of dollars per year; a perception that student learning is facilitated by AI and algorithms rather than human professionals can damage crucial stakeholder relationships. According to the article, it’s concealed or excessive teacher use of AI that has the potential to erode the relationship of trust.

Of course, we’ve long known about the correlation between students’ positive, trusting relationships with their teachers and improved learning outcomes (Sabar, 2024; McKay & McComber, 2021; Fisher & Frey, 2019; Pierson, 2013). So, what happens to those trusting relationships when teachers use AI in their lesson planning and grading? Like the Terminator, AI is devoid of emotion and can only follow human-given instructions. Only people have the ability to be wise and ethical, to be caring mentors and role models. So, are the gasping, chest-clutching colleagues right to believe that teacher use of AI is unethical and “does more harm than good?” Perhaps. Perhaps not. Like any tool—technological or otherwise—the potential for harm or benefit lies in the hands of the user. Terminators don’t harm people; people harm people, right? The same goes for generative AI.

Policies, Pitfalls, and the Need for Continuous Dialogue

To minimize unethical and potentially harmful use of AI, schools, districts, and universities have been developing usage policies for both students and faculty members. Some of these policies are reactive and have overly restrictive parameters whereas others provide educators with very little useful guidance. Neither extreme invites people to think deeply or have meaningful conversations that could lead to growth and personal insights about the ethics of how they’re using generative AI now or in the future. Fortunately, some organizations, such as James Madison University, have more effective, fluid guides that are designed to evolve and to engage faculty members in ongoing dialogue and critical evaluation as AI continues to expand within the educational landscape.

A Balanced Approach to Ethical GenAI Use by Teachers

To stay future-ready, schools can follow James Madison University’s example by guiding faculty members toward a thoughtful middle ground—one rooted in ethical reflection and professional dialogue—rather than defaulting to a binary “use it” or “don’t use it” stance on teacher use of generative AI. This balanced approach lies between the extremes of prohibiting teacher use of AI and allowing unrestricted, unexamined use. In this approach, AI becomes a tool that supports rather than detracts from student learning and growth. Teachers can retain agency, exercise professional judgment, and be equipped with the guidance they need to navigate the ethical complexities of AI in education. Schools can navigate teacher use of generative AI as true learning communities of collaborative professionals—not as chaotic free-for-alls or rule-bound factories run by bossy bosses with volumes of rigid rules.

Individual educators, teaching teams, and professional learning communities (PLCs) would benefit from decision-making frameworks, essential questions, and discussion starters to guide thoughtful, ethical choices about how to use AI in their practice. When developing these supports for educators, school leaders can draw inspiration from two promising tools designed to guide students’ ethical use of generative AI.

Promising Tools to Generate Thinking and Ongoing Discourse

The AI Assessment Scale (AIAS) (Furze, et. al. 2024) and AI Indicator (Barker, 2025) go beyond lists of rules for AI use. Instead, they foster student agency, responsibility, and accountability; they prepare learners to make thoughtful decisions, use AI ethically, and focus on asking the right questions. As similar tools emerge, it's essential to consider the ethical implications in education.

AIAS, developed by Leon Furze, Mike Perkins, Jasper Roe, and Jason MacVaugh, is a framework designed to guide educators in integrating generative AI (GenAI) into educational assessments. The AIAS outlines five levels of AI integration, ranging from no AI involvement to full AI utilization, allowing educators to align AI use with specific learning outcomes and assessment goals. This structured approach facilitates clarity and transparency for both educators and students, promoting ethical and effective use of AI tools in learning and assessment.

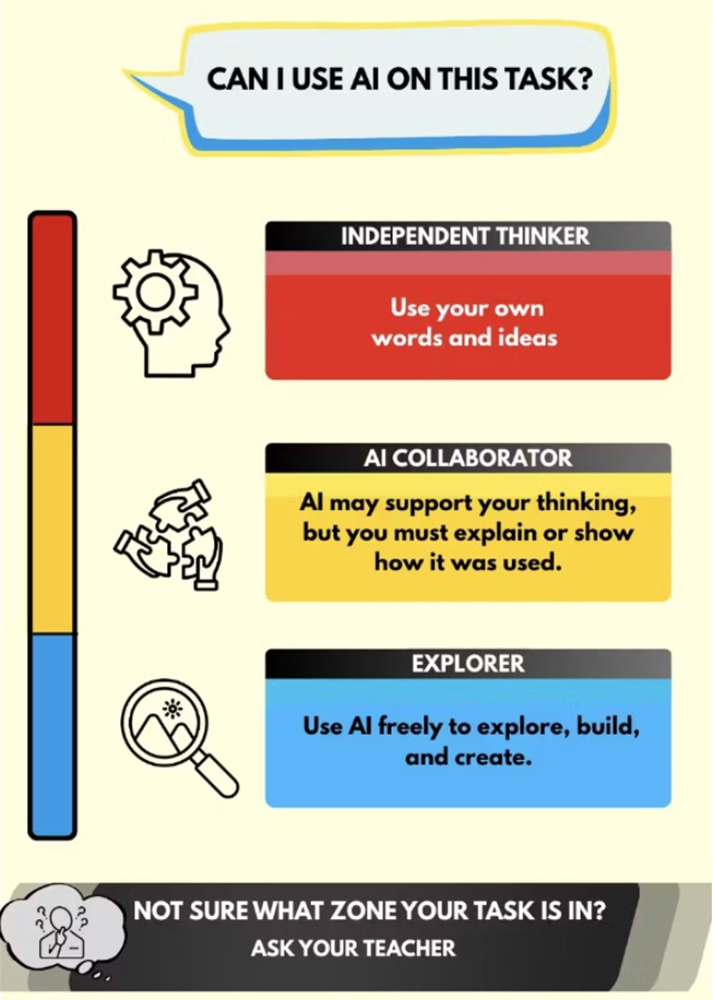

AI Indicator (Photo source: Megel Barker, 2025)

Similarly, Megel Barker’s AI Indicator is a streamlined framework to provide clarity and shared understanding among students, educators, and parents in ethical and effective student use of generative AI. Barker proposes a three-tiered system that categorizes AI usage based on the nature of the task and the desired learning outcomes. This framework incorporates a student-friendly color-coded system to help eliminate ambiguity around generative AI use in assignments. By aligning AI usage with specific educational objectives, the AI Indicator can be used to foster academic integrity when using advanced technologies.

The AIAS and AI Indicator promote agency, responsibility, and accountability. Rather than giving learners rules to follow blindly, they prepare them for independent decision-making in the future. Similarly, effective frameworks for teacher use of generative AI will engage educators in asking essential ethical questions. So how do we define what’s “ethical” in the first place?

Ethical Paradigms and the Ethic of the Profession

In the latter half of the 20th century, the role of ethics in education, particularly within leadership, was influenced by scholars and theorists such as Starratt, Sergiovanni, Noddings, Freire, and Capper. Building on the foundational work, 21st century thinkers including Tschannen-Moran, Kutsyuruba and Walker, Kouzes and Posner, Ciulla, and Berkovich and Eyal continue to advance the conversation through research and theory. Collectively, these scholars suggest that ethical dilemmas in education can be understood through at least three key paradigms: the ethics of Justice, Critique, and Care.

The Ethic of Justice pertains to human rights and freedoms, equality and fairness, and law and order. The Ethic of Care incorporates benevolence, treatment, concern, social responsibility, and morality. The Ethic of Critique is grounded in principles and critical theory. It involves analyzing inequities and the fairness of laws and cultural practices.

Shapiro and Stefkovich (2022) emphasize a fourth ethical paradigm in educational leadership: the Ethic of the Profession. This paradigm acknowledges the indispensability of the other three key paradigms, while emphasizing that ethical decisions in education must be informed by the expectations embedded in the professional responsibilities of educators. Ethical leaders are expected to serve their communities with integrity and transparency, recognizing the far-reaching implications of their actions. By following a strong ethical code, leaders foster trust and collaboration—essential for effective educational environments.

Most, if not all, published codes of ethics for educators are underpinned by a central commitment to student learning and wellbeing. For example, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2019) asserts, “Our responsibility is to build a trusting relationship with those we work for and with. Our loyalty rests with the children and the pupils, to promote what is in their best interest. Truthful communication of knowledge and high quality pedagogical facilitation is essential” (p. 3). Similarly, the National Education Association (NEA) in the United States emphasizes that “the educator… works to stimulate the spirit of inquiry, the acquisition of knowledge and understanding, and the thoughtful formulation of worthy goals” (NEA, 2020, para. 1). The Ontario College of Teachers (OCT) underscores that “members apply professional knowledge and experience to promote student learning. They use appropriate pedagogy, assessment and evaluation, resources and technology in planning for and responding to the needs of individual students and learning communities” (OCT, n.d., para. 2).

All four ethical paradigms, but especially the Ethic of the Profession, can inform educators’ decisions about best use of AI in their work. These paradigms can also guide ongoing PLC discussions in your school or district. Shapiro and Stefkovich (2022) identified important discussion and decision-making questions for the paradigms:

Ethic of Justice: Is there a law (or rule), right, or policy that relates to a particular case? If there is a law, right, or policy, should it be enforced? And if there is not a law, right, or policy, should there be one?

Ethic of Critique: Who makes the laws? Who benefits from the law, rule, or policy? Who has the power? Who are the silenced voices?

Ethic of Care: Who will benefit from what I decide? Who will be hurt by my actions? What are the long-term effects of a decision I make today? If I am helped by someone today, what should I do in the future about giving back to this individual or to society in general?

In discussing the Ethic of the Education Profession, Shapiro and Stefkovich emphasized placing “students at the center of the ethical decision-making process” (2024, p. 27). Progressive schools and school systems have policies in place to support social and emotional wellness for all and to provide a supportive, fair, equitable learning environment free of discrimination. With that in mind, some additional discussion and decision-making questions could be:

There’s so much to consider! No wonder some organizations opt for the perceived safety of a zero-use policy for faculty. However, a schoolwide ban on AI use is about as effective as trying to lower incidences of teen pregnancy by eliminating sex ed programs. A more realistic approach is to create a framework for ongoing discussions and continuing ethical decision-making that fits your school or district.

Helping Teachers Use AI Wisely and Ethically: Building Your School’s Framework

As convenient and tempting as it might be to implement a framework that can be rigidly applied across all schools and contexts, education isn’t a plug-and-play profession. We’re in the learning business, which means we’re in the people business. Every school and district is as unique as the community it serves, and every community is made up of individuals who deserve high-impact, personalized learning opportunities in a safe, supportive environment. This pertains to our faculty members as much as it does to our students. Simply put, our work is far too complex for prepackaged solutions, or anything pulled off the rack. Context is a crucial consideration.

Individual educators, teaching teams, and PLCs would benefit from a framework that includes essential questions and discussion starters to guide thoughtful, ethical choices about how to use AI in their practice. Here are steps your school can follow to develop a framework that’s flexible, evolving, and personalized for your school community and context.

Step 1: Establishing consensus

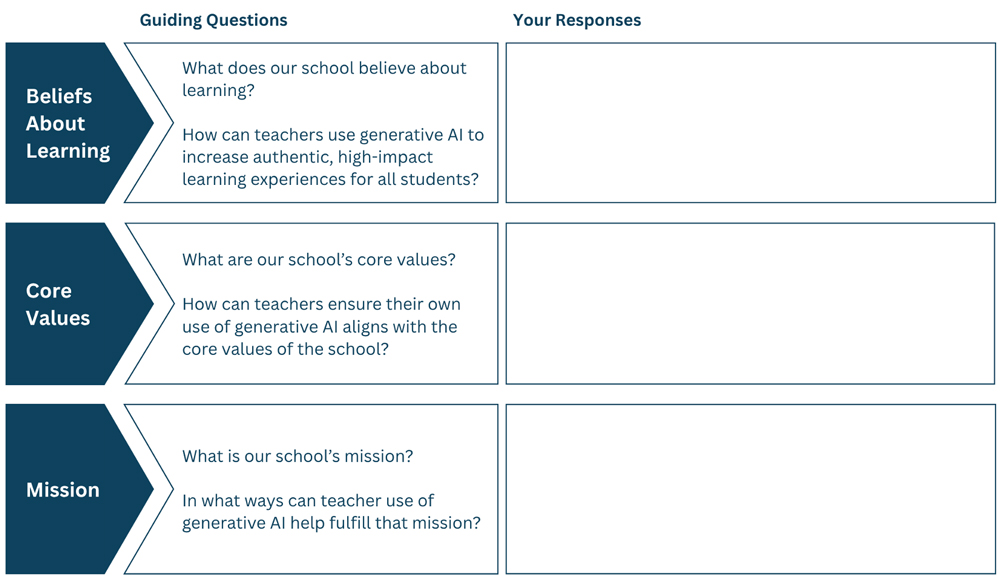

Initial conversations should engage leaders and faculty members in a deep dive of guiding questions. The answers will underpin all future decisions about teachers’ use of generative AI. Below are three suggested guiding questions:

Step 2: Creating broad policies for teacher use of AI

The answers to the guiding questions will inform your conversations and eventual decisions about developing policies and guidelines for your faculty. As you develop policies, consider essential ethical questions. The sample questions below are based on the Ethical Paradigms of Justice and Critique. What additional essential ethical questions should be added to fit your school’s unique context?

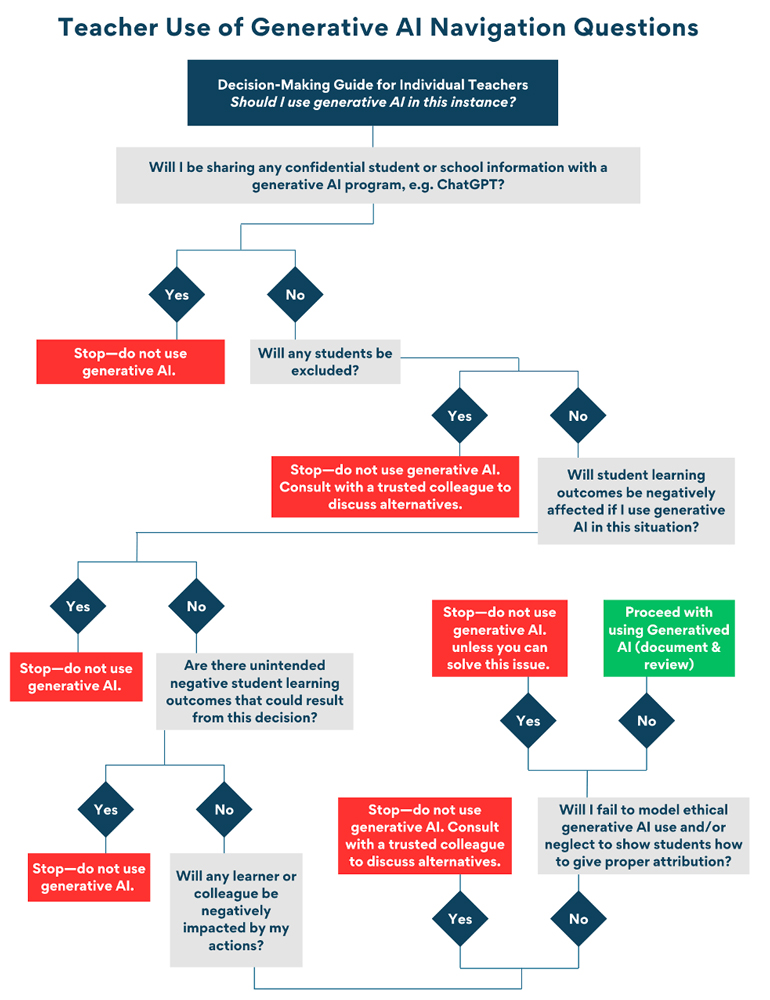

Step 3: Decision-making Guide for Individual Teachers; Navigation Questions

After your school has established the broad policies to guide teachers’ use of AI, the next step is to equip your teachers with a quick reference guide they can use on a case-by-case basis to determine whether it would be acceptable and advisable for them to use Generative AI. The example below draws upon Shapiro and Stefkovich’s (2022) ethical decision-making questions and the Ethic of the Education Profession. It’s important to note that the Stop signs are not an indication that the use of AI is completely off the table. Instead, the idea is to resolve or solve the issue before trying again.

At regular intervals, the following questions, and other questions as they arise, should be explored and discussed among colleagues via PLCs, instructional teams, or committees. Regular data reviews will inform the responses.

Several organizations have raised concerns about GenAI’s environmental impact (Elizabeth City University, n.d.; United Nations Environment Program, 2024; Zewe, 2025).

Teachers’ effective and ethical use of generative AI will require an ongoing, reflective process. This is a journey without a final destination and will require careful attention to data, regular conversations with colleagues, and a deep understanding of what makes each school community and learner unique. AI can be a powerful tool, but its use should be guided by human judgment, ethical thinking, and shared values. The framework offered here shouldn’t be viewed as prescriptive or as a rigid set of rules. Instead, it’s a flexible guide designed to facilitate professional judgment, align with your school’s mission, and support ongoing professional discussions and ethical practice. We can hardly imagine how generative AI will advance in the future or how embedded it will eventually become in our students’ daily lives. A few things are certain, though: AI cannot be held accountable, humans must bear that responsibility. And, unlike the Terminator-800 model, human wisdom and discretion can never become obsolete.

Footnote: In case you’re wondering whether I used generative AI as I wrote this, of course I did! I also don’t make waffle batter from scratch if I can get my hands on a box of Krusteaz® mix. Do you? Here's a disclosure of what I asked AI. Note that I did say “please” and “thanks” just in case machines do take over the world someday.

AI doesn’t know everything, though. Fortunately, I have my young adult kids for that (wink). For perceptive and insightful feedback on this blog, I turned to human thinkers including some insightful colleagues at PLS 3rd Learning® and my laser-witted daughter and son. Thank you, Breanne Callahan, for the graphics!

References

Barker, M. (2025). Promoting responsible generative AI use in schools. TIE Online. https://www.tieonline.com/article/7594/promoting-responsible-generative-ai-use-in-schools?nid=78

Carnegie Learning. (2024). The state of AI in education 2025 [PDF]. Carnegie Learning. Retrieved from https://discover.carnegielearning.com/hubfs/PDFs/2024-AI-in-Ed-Report.pdf

Elizabeth City University. (n.d.). Environmental impacts – A guide to Artificial Intelligence (AI) for students. ECU LibGuides. Retrieved June 26, 2025, from https://libguides.ecu.edu/c.php?g=1395131&p=10318505

Farmingdale Observer. (2025, May 27). Mobile phones were banned… Farmingdale Observer. https://farmingdale-observer.com/2025/05/27/mobile-phones-were-b

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2019). The formative assessment action plan: Practical steps to more successful teaching and learning. ASCD.

Furze, L. (2024, August 28). Updating the AI assessment scale. Leon Furze. https://leonfurze.com/2024/08/28/updating-the-ai-assessment-scale/

Inside Higher Ed. (2024, June 28). One-third of college instructors are using GenAI—here’s how. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/student-success/academic-life/2024/06/28/one-third-college-instructors-are-using-genai-heres

James Madison University Libraries. (n.d.). Ethics of AI in education. James Madison University Libraries. https://guides.lib.jmu.edu/AI-in-education/ethics

Langreo, L. (2025, March). More teachers say they’re using AI in their lessons. Here’s how. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/technology/more-teachers-say-theyre-using-ai-in-their-lessons-heres-how/2025/03

McKay, K., & McComber, H. (2021). The importance of relationships in education: Reflections of current educators. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357009315_The_Importance_of_Relationships_in_Education_Reflections_of_Current_Educators

National Education Association. (2020). Code of ethics for educators. National Education Association. https://www.nea.org/resource-library/code-ethics-educators

Ontario College of Teachers. (n.d.). Standards of practice for the teaching profession. Ontario College of Teachers. https://www.oct.ca/public/professional-standards/standards-of-practice

Pew Research Center. (2024, May 15). A quarter of U.S. teachers say AI tools do more harm than good in K-12 education. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/05/15/a-quarter-of-u-s-teachers-say-ai-tools-do-more-harm-than-good-in-k-12-education/

Pierson, R. (2013, May). Every kid needs a champion [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/rita_pierson_every_kid_needs_a_champion

Sabar, L. (2024). Formative feedback in the age of AI: Real-time data and deeper learning. Harvard Education Press.

Sabbar, S. (2024). Examining the significance of trust and respect in teacher-student relationships and their effects on student motivation in EFL contexts. Thi Qar Arts Journal, 2(45), 52. https://doi.org/10.32792/tqartj.v2i45.552

Shapiro, J. P., & Stefkovich, J. A. (2022). Ethical leadership and decision making in education: Applying theoretical perspectives to complex dilemmas (5th ed.). Routledge.

Slagg, A. (2024, September 30). AI in Education in 2024: Educators express mixed feelings on the technology’s future. EdTech Magazine. Retrieved from https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2024/09/ai-education-2024-educators-express-mixed-feelings-technologys-future-perfcon

Tyton Partners. (2025). Racing forward: Bridging the gap between generative AI proficiency and educational practice. https://tytonpartners.com/racing-forward-bridging-the-gap-between-generative-ai-proficiency-and-educational-practice/

UNESCO. (2019). Professional ethics for the teaching profession: A policy document. UNESCO. https://etico.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/norway_xx_professional_ethics_for_the_teaching_profession.pdf

United Nations Environment Programme. (2024, September 21). AI has an environmental problem. Here’s what the world can do about that. UNEP. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/ai-has-environmental-problem-heres-what-world-can-do-about

What students are saying about teachers using A.I. to grade. (n.d.). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/18/learning/what-students-are-saying-about-teachers-using-ai-to-grade.html

Zewe, A. (2025, January 17). Explained: Generative AI’s environmental impact.?MIT News. https://news.mit.edu/2025/explained-generative-ai-environmental-impact-0117

Kelly Mekdeci is dedicated to advancing education and enhancing school performance through collaborative partnerships and high-quality professional learning for educators. Currently, Dr. Mekdeci serves as the Senior Vice President for Professional Growth at PLS 3rd Learning and is an instructor for the Association for the Advancement of International Education (AAIE) Institute. As an international school Head, governance consultant, and accreditation lead evaluator, she has supported over 30 schools and organizations in the United States of America, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Middle East. As a course designer and adjunct professor, her work focuses on fostering ethical school cultures, student achievement, and social-emotional wellbeing.