In the first article in this series in TIE we looked at building a new relationship with parents, no longer thinking of ourselves as “educating” them and instead intentionally building learning communities with them. Now to apply the same kind of thinking to our teachers….

I don’t know about you, but I never did good work because someone was “supervising” me. We do good work for its own sake, or perhaps even more significantly, for the sake of the learners and “learning families” whom we serve…the people who drew us into the learning profession in the first place. I suspect that many of us feel the same way….and yet our profession is loaded with the language and failed practice of “supervision.”

I believe most of that practice is rooted in a way of thinking that simply doesn’t work…and never did. That “doesn’t work” statement needs some qualification. It doesn’t work if we believe that our primary purpose is improving learning by informing practice. To state the blindingly obvious, beyond our learners, our teachers are our greatest asset. They are the heart of our schools. The quality of learning depends upon the quality of teaching, and I don’t believe you can control people into quality.

We often hear that the biggest problem with “change” in schools is time, or the lack of it. I’d suggest that the biggest problem is actually energy. It’s a precious and limited resource, and yet we waste vast amounts of it on teacher supervision/evaluation processes that simply don’t produce a learning impact to justify the energy expenditure. Not enough learning bang for the energy buck. Most of these “systems” don’t even start in the right place…by determining a learning impact sufficiently substantive to justify the energy expended. We look at teachers instead of looking for learning.

So, where would that energy be better spent? There’s a clear enough answer. We’d be better off creating learning cultures, deep, co-created approaches to “the way we do things around here,” a simple definition of “culture” that works just fine. Another memorable definition that sums up the thread of this thinking is, “Culture is what we do when nobody’s watching.” Surely that is the actual purpose of working on improving practice. We will do what is best for learning, without anyone “supervising” us.

Most of the off-the-shelf, adopted supervision models focus on supplying “standards” for teachers, and then “evaluating” teachers against those standards. We then spend energy convincing teachers that these standards are descriptors of how they should behave. It’s all very compliance-oriented and rule-bound. It’s compounded by the inevitable flaws built into the system. If, along with Michael Fullan, we believe that “We are all sense-makers and our best sense-making tool is conversation,” then there simply aren’t enough “supervisors” to go around…if deep learning conversations are the goal. If we compound that by expecting teachers to write multiple personal goals each year, then the chances of digging into those goals are further minimized. In Common Ground Collaborative (CGC), we refer to that process as “letters to Santa.” In contrast, we have experienced rapid, deep transformation in schools as a result of working together as a faculty on one collective annual goal of high learning impact for all students. It’s a simpler, more effective use of time and energy.

When we add up these elements: the compliance language, the energy expenditure with relative lack of impact, the “here’s another system for evaluating you,” the lack of possible follow-through in terms of deep conversations and consistent, precise, actionable feedback…the list goes on…and it’s a small wonder that teachers tend to have little faith in supervision systems. They know they have to go through the process, but they know their time and energy can be better spent elsewhere…where it makes a learning difference.

They know they have to go through the process, but they know their time and energy can be better spent elsewhere…where it makes a learning difference.

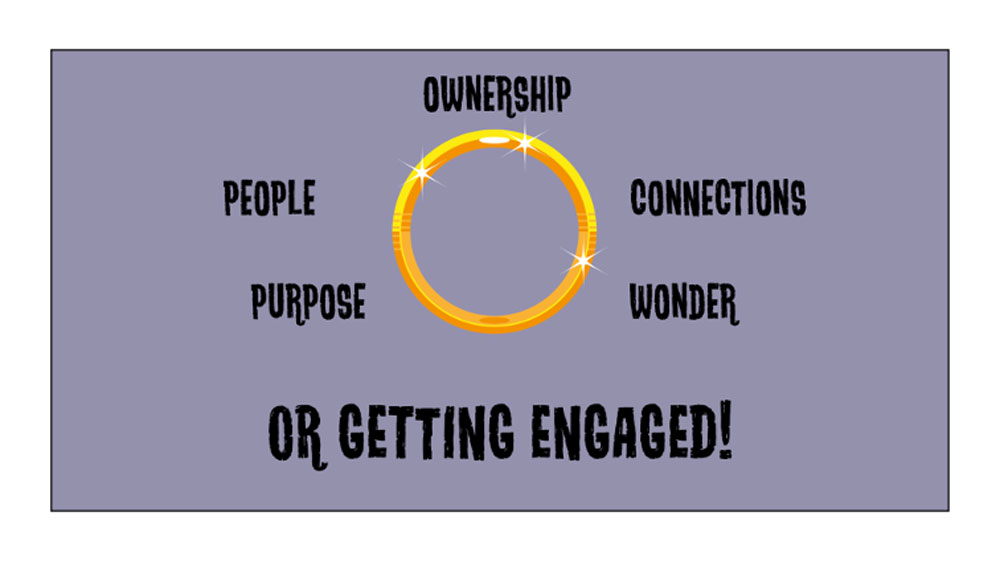

In CGC, we take a different approach to improving learning by informing practice. We see schools as learning cultures and believe that cultures are framed by shared principles, not constrained by imposed rules. We define a principle as “a shared truth that brings order and freedom to a system.”

So, where do our Learning Principles come from? They come from within us. That’s why we believe in them. We work with teachers to dig deeply into their own learning experiences…as learners, usually as children. The good, the bad, the ugly. We tell our stories. We unearth the messages in those stories. We turn those messages into principles for our profession…the things we should never forget. We believe that a well-crafted, co-created set of Learning Principles will be a practical synthesis of our shared learning experiences and the most reliable research on what works best. As always in CGC, we also believe in simplicity over complexity, so we generally work hard to synthesize our collective wisdom into four to five Learning Principles, and we find that this is plenty to guide learning, teaching and leading. The graphic included here is simply an example, as schools develop their own Principles, albeit with frequent, substantive similarities. To us, common sense alone dictates that, as professionals, we are more likely to follow a “shared truth” than to attempt to comply with the mind-boggling number of standards that seem to over-populate evaluation systems. When we teach on principle, we are engaged with those principles.

Of course, a set of Learning Principles has no value on its own. Just another wall adornment to nail up by the Mission Statement. The real learning impact comes when Learning Principles are translated into Learning Practices, then into the necessary Teaching Practices to support the learning, then Leading Practices to support the teaching. It’s basic logic, a simple if-then syllogism: If we are living this principle, then here’s what we’ll see our learners doing, here’s what our teachers will be doing in support, and here’s what our leaders will be doing to sustain this culture of “learning, teaching and leading on principle.” To re-emphasize the point, we include in our “practices” the key approaches that research shows have the greatest learning impact…so not everything is co-created on the ground in a school…and, of course, our smart teachers are just fine with that. They are, in effect, creating a new ‘job description’, but not a functional transactional model, a deep, transformational model.

Of course, a set of Learning Principles has no value on its own. Just another wall adornment to nail up by the Mission Statement. The real learning impact comes when Learning Principles are translated into Learning Practices, then into the necessary Teaching Practices to support the learning, then Leading Practices to support the teaching. It’s basic logic, a simple if-then syllogism: If we are living this principle, then here’s what we’ll see our learners doing, here’s what our teachers will be doing in support, and here’s what our leaders will be doing to sustain this culture of “learning, teaching and leading on principle.” To re-emphasize the point, we include in our “practices” the key approaches that research shows have the greatest learning impact…so not everything is co-created on the ground in a school…and, of course, our smart teachers are just fine with that. They are, in effect, creating a new ‘job description’, but not a functional transactional model, a deep, transformational model.

So, that’s the idea. We begin with the simple belief that, to get better at something, we have to learn to get better at it. So, we need to come at improving our practice from a learning angle, not a supervision angle. We need to take the time, and expend our energy, co-creating a school-wide learning culture shaped by a few deeply held shared learning principles that drive our practices for learning, teaching, and leading.

In summary, we need to demolish the industrial language of “supervision,” loaded with messages of compliance, with the learning language of teaching, learning, and leading on principle. Then we’ll start to see the learning impact our learners deserve.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------Kevin is the Founding Director of Common Ground Collaborative.